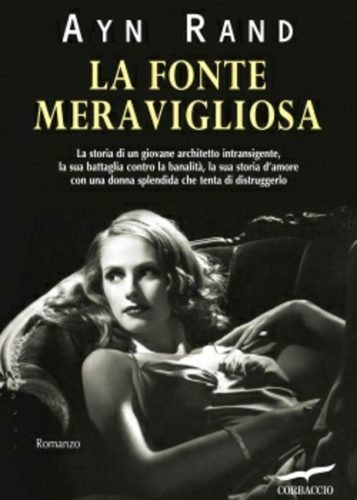

I can think of Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and to John Donne’s lyrics, whence the title. No man is an island, and men’s dependance is mutual. Nothing further from what Ayn Rand maintained in The Fountainhead, published in 1943. The protagonist is a man who is above other, a hero who may suffer, but won’t give up on his credo, and fights angrily to keep true to it. Inspired by the life of the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, his figure wouldn’t be well received by today’s environmentalists. The protagonist looks at a cliff and sees construction material, he looks at trees and sees lumber. And yet, the novel is pervertedly fascinating. It contains all ingredients of a great nineteenth-century story: a hero who unwaveringly fights against all opponents, perfidious friends turning into enemies, powerful businessmen, a woman who never experiences love but maintains a destructive relationship, the usual office conspiracies, the self-made man–all in the burgeoning New York of skyscrapers. No sex: this is America at a time when Alfred Kinsey had yet to publish his research.

The director of The Childhood of a Leader (2015) and Vox Lux, both presented at the Venice Film Festival, returns to Venice with a new film shot in 70mm, depicting the life of a visionary architect who is resistant to compromise. László Toth, a ...

The Fountainhead is also the book Ayn Rand uses to state her philosophy. Born Alisa Rozenbaum in Russia, she migrated early to the United States and founded a philosophical current, objectivism, recently rehabilitated with Trump. The Fountainhead is the human mind, who is to be kept free to create. The tenets of this philosophy is that “individual happiness is the goal of life, productive success is its most noble activity” and that freedom and obligation are not antithetical. The book provides traffic lights as an example: a red light sets you free from the risk of being hit by a truck. The rest of the story is in style. Every page is, in fact, a great film sequence. Rand studied film in Russia. Her script for Red Pawn (1932) determined her Hollywood success. Her novel We the Living was adapted in two Italian films, both released in 1942. Both were praised, initially, for their anti-communism, then censored because they were anti-totalitarian. There’s nothing easier to adapt to film than Ayn Rand’s books. Brady Corbet did as much with The Brutalist.