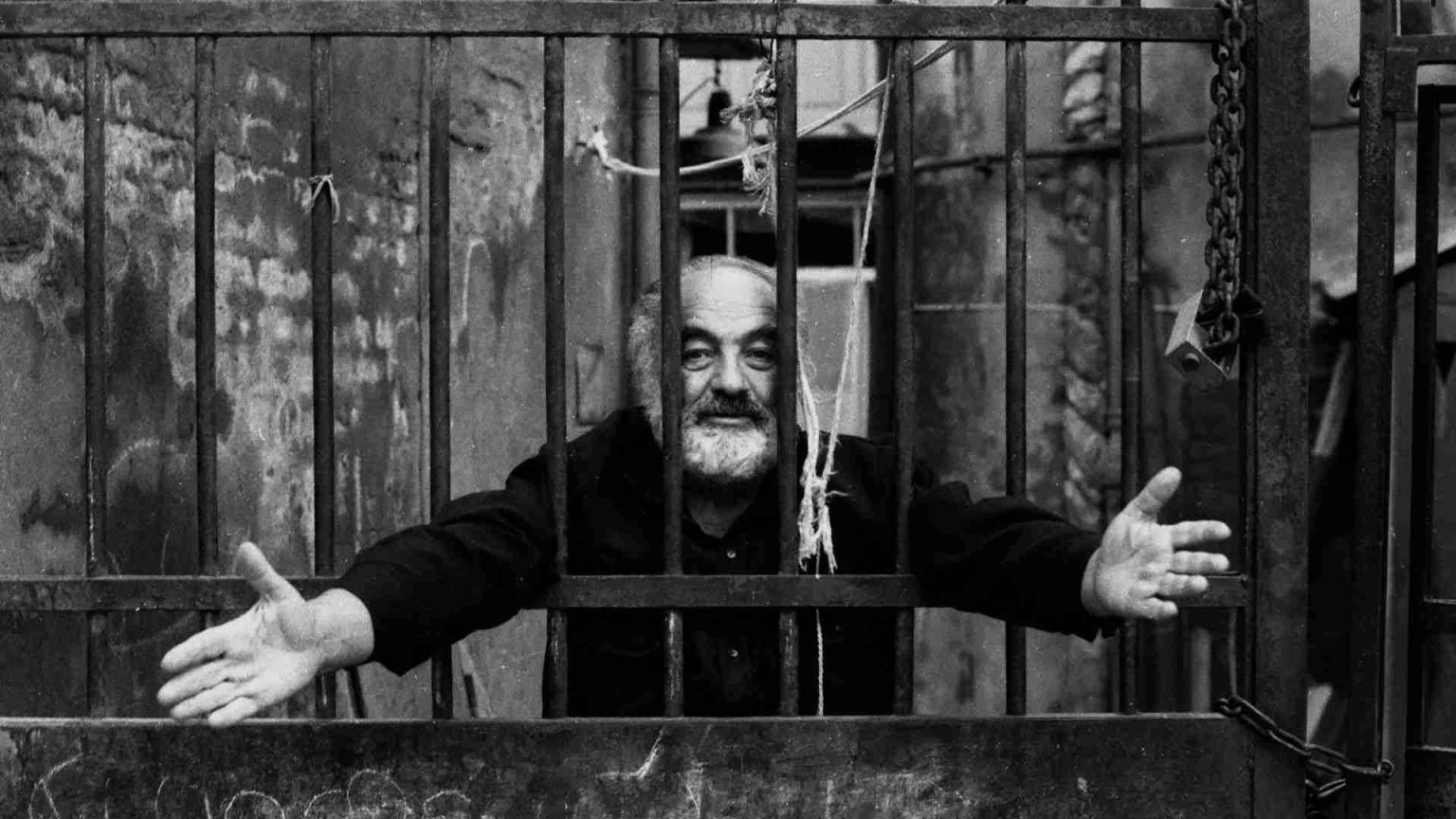

On the tenth anniversary of his birth, the great Armenian filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov is remembered in a docudrama by young director, producer and actress Zara Jian. Despite being opposed throughout his whole life because of his films, which didn’t follow the prec...

Sergei Parajanov belongs to the small filmmaking squad that not only created masterpieces, but also defined a new language for cinema, that is, a new way to mix images, sound, words. Born in Tbilisi to Armenian parents, Parajanov studied film in Moscow to later find work in Kiev. In his first ten years as a professional filmmaker, he directed documentaries, short movies, and features inspired by the solid tradition of 1950s-era Russian Realism. Now, it is true that Parajanov disavowed thos films, up to calling them ‘garbage’, but we cannot agree with him up to that point. Kafka had the same opinion about himself, and we do well to ignore that bit. I will say, and firmly stand by, that Ukrainian Rhapsody, Flower on the Stone, The First Lad, all released between 1959 and 1962, are great movies, and glimpses of Parajanov’s future genius are clearly visible. Look at the initial scene in the sunflower field in The First Lad, there you’ll find the essence of that visual ecstasy that will become the filmmaker’s signature move.

With Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors of 1964, Sergei Parajanov matured to that level of expressive freedom that allowed him to create an absolute artwork, a radical overlaying of images, words, and sound, a work of narration and religious symbolism, history, religion, and ethnography. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is a treadmill of images, feelings, sounds, framed in such perfect footage, itself continuously moving between wide shot and exasperated close-ups, though always keeping a definitely linear structure of narration, however loose.

This won’t be there at all in his following masterpiece, five years later: The Color of Pomegranates, an eight-minute sequence of tableaux vivants of glistering beauty: bodies, animals, objects, religious items telling the story of eighteenth-century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova. That was too much for Soviet censors: after all, the Soviet thaw had stopped a few years prior with Khrushchev’s death. The film was pulled and Parajanov was arrested in 1974. In 1977, authorities released him; in 1982, they arrested him again. For fifteen years, it was impossible for him to work. Before his death in 1990, he has been finally able to make two last great movies: The Legend of Suram Fortress and Ashik Kerib – The Lovelorn Minstrel, the final testimony of a genius of life and of film.