After Spira Mirabilis (2016) and War and Peace (2020), the documentary filmmaking duo returns to the Lido with Bestiaries, Herbaria, Lapidaries, screening Out of Competition. This work is a cinematic and poetic encyclopaedia, divided into three acts, each made in the distinctive style of a particular documentary language.

How did these “strangers”… like animals, plants and minerals become the subject of your work? And how is human action represented through them?

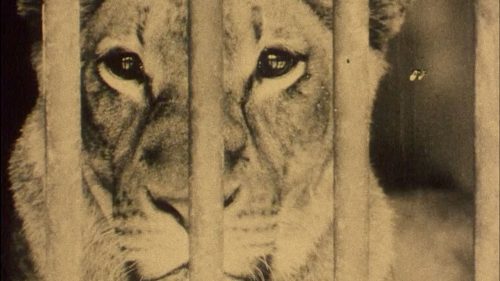

We have wanted to make a film about the plant world for a long time. However, plants are difficult to conceptualize and even harder to film, so the project remained on hold. However, like something in a karst landscape, the idea kept resurfacing. In autumn 2020, after our participation in the Venice Film Festival with War and Peace, we began thinking about our next film. However, the world was still shut down due to COVID, which greatly limited our possibilities. Our imagination was fertile, but mobility restrictions were a constant challenge. We considered limiting the film’s scope to Milan, the city where we live. Then, one day, a friend mentioned that two newborn tigers with pneumonia were hospitalized at the neighbourhood veterinarian. We went to see them immediately and were captivated. This encounter led us to connect animals and plants, and the title Bestiaries, Herbaria started to take shape. Following medieval tradition, we added stones to the concept, and thus the first treatment was born: Bestiaries, Herbaria, City Lapidaries. We aimed to complete the film within a year, which was ambitious for us. But as the world began to reopen, the project expanded beyond the city’s boundaries. Four years later, Bestiaries, Herbaria, Lapidaries was complete, a film where human actions are intricately woven into the natural world we portray.

The film is a sort of cinematic and poetic encyclopedia divided into three acts, each dedicated to a single subject: animals, plants, and stones. Each act is also a tribute to a specific genre of documentary cinema, ranging from found footage, including images from Roald Amund...

A film that evolves into a scientific treatise, bridging the ancient and the contemporary, with a unique dramaturgical approach and three different staging techniques. How did you structure the film to address such an encyclopaedic topic?

From the very beginning, the film unites the three kingdoms of nature. We assigned each kingdom a documentary language: the archival film presented as an essay, the poetic and observational documentary, and the industrial and sentimental film. The result is an “encyclopaedia” that blends cinema, nature, and emotions. Our films are always long journeys during production, and the encyclopaedic form, in its own way, represents a journey into knowledge. We aimed to interpret, convey, and represent this wonderful world, where we transform reality and emotions into film.

Documentaries are increasingly taking centre stage at festivals. A genre that, until recently, might have seemed confined within strict boundaries, today acquires a full and multifaceted freedom of form and language. What makes this genre unique and essential for you?

We believe that documentary cinema offers an unlimited freedom of thought and depth of exploration, enabling us to continuously learn from the world, from encounters, and from the gifts of “chance”. It is the form of cinema that best represents us, both in terms of production and creativity.