De’ Visi Mostruosi e Caricature. Da Leonardo Da Vinci a Bacon is a surprising exhibition, powerful and delicate, one you’d love to see. It will be open at Palazzo Loredan until April 27. The curator of the exhibition is Pietro C. Marani, one of the most renowned experts on this topic and on Leonardo overall.

“Mankind had always been at the centre of our interest” says Inti Ligabue, chairman of Fondazione Giancarlo Ligabue. Their current exhibition circles about a woman, to be precise: around a drawing by Leonardo, Head of old woman, that fascinated Giancarlo and that Inti placed as starter piece of a new, incredible journey.

The gaunt face of a toothless old woman, her nose flattened up against her forehead, droopy lips, a couple extra chins, wrinkly skin, her hair pulled back into a veil adjusted with a flower, in stark contrast with her obviously old age. It wasn’t irony or mockery that inspired Leonardo: this was a study of caricature, a study of physiognomy, and research for a kind of realism that investigated the morals and virtues of the portrayed.

Other than the head of the old woman, there are eighteen further drawings by Leonardo, with some of those being in Italy for the very first time. The exhibition will trace and study the development of a charming art genre – caricature. De’ Visi Mostruosi e Caricature. Da Leonardo Da Vinci a Bacon is a surprising exhibition, powerful and delicate, one you’d love to see. It will be open at Palazzo Loredan until April 27. The curator of the exhibition is Pietro C. Marani, one of the most renowned experts on this topic and on Leonardo overall, who worked with Alessia Alberti, Luca Massimo Barbero, Paola Cordera, Inti Ligabue, Enrico Lucchese, Alice Martin, Alberto Rocca, Calvin Winner.

Caricatures and realistic portrait of deformed faces

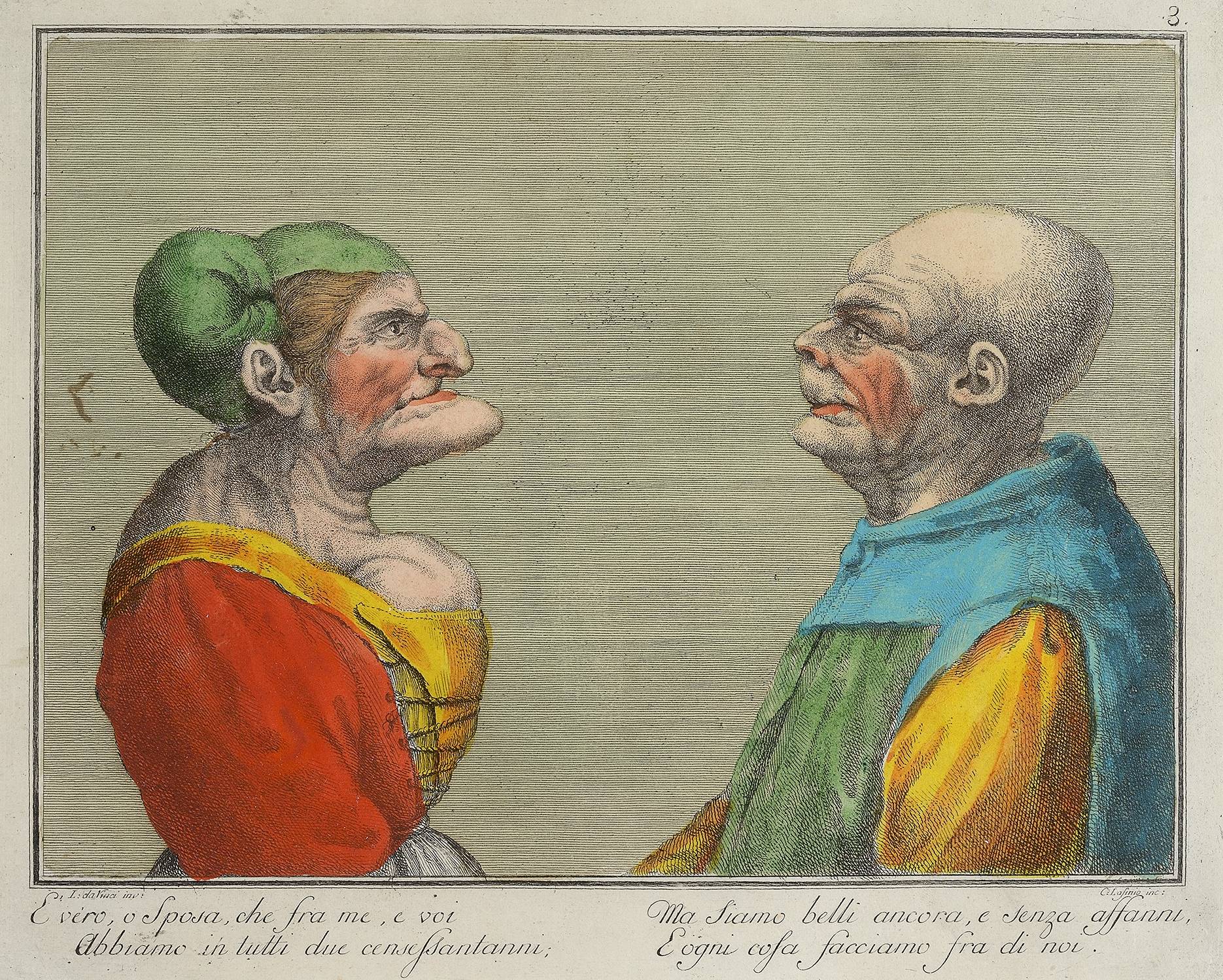

The art of caricature and the truthlike depiction of deformed faces are different things obviously. The latter has been attested in fifteenth-century Florence, the continuation of the Medieval tradition and usage of grotesque, monstruous figures to decorate Gothic cathedrals. Leonardo participated in this cultural trend in that his heads are monstrous and caricate (‘charged’ or ‘loaded’) with moral intentions or societal critique as a counterpoint to the ideally beautiful and morally good. Caricature, on the other hand, emerged much later and its goal is to play and entertain. This is not to say the two traditions can sometimes influence one another and overlap.

The deformity of the soul

‘Charged’ heads may allude to the passing of time, which turns the beautiful into the hideous. In this sense, Leonardo, but also Giorgione, frankly depicted Time as the corruptor of Beauty. In Leonardo’s drawings, we can often see young and nimble characters opposing old men and women, their bodies ravished by age. It is my opinion that we cannot use this art to make any psychological evaluation, though some did interpret them as the product of some autobiographical or psychological outpour of Leonardo’s mind.

Other artists who followed the trend

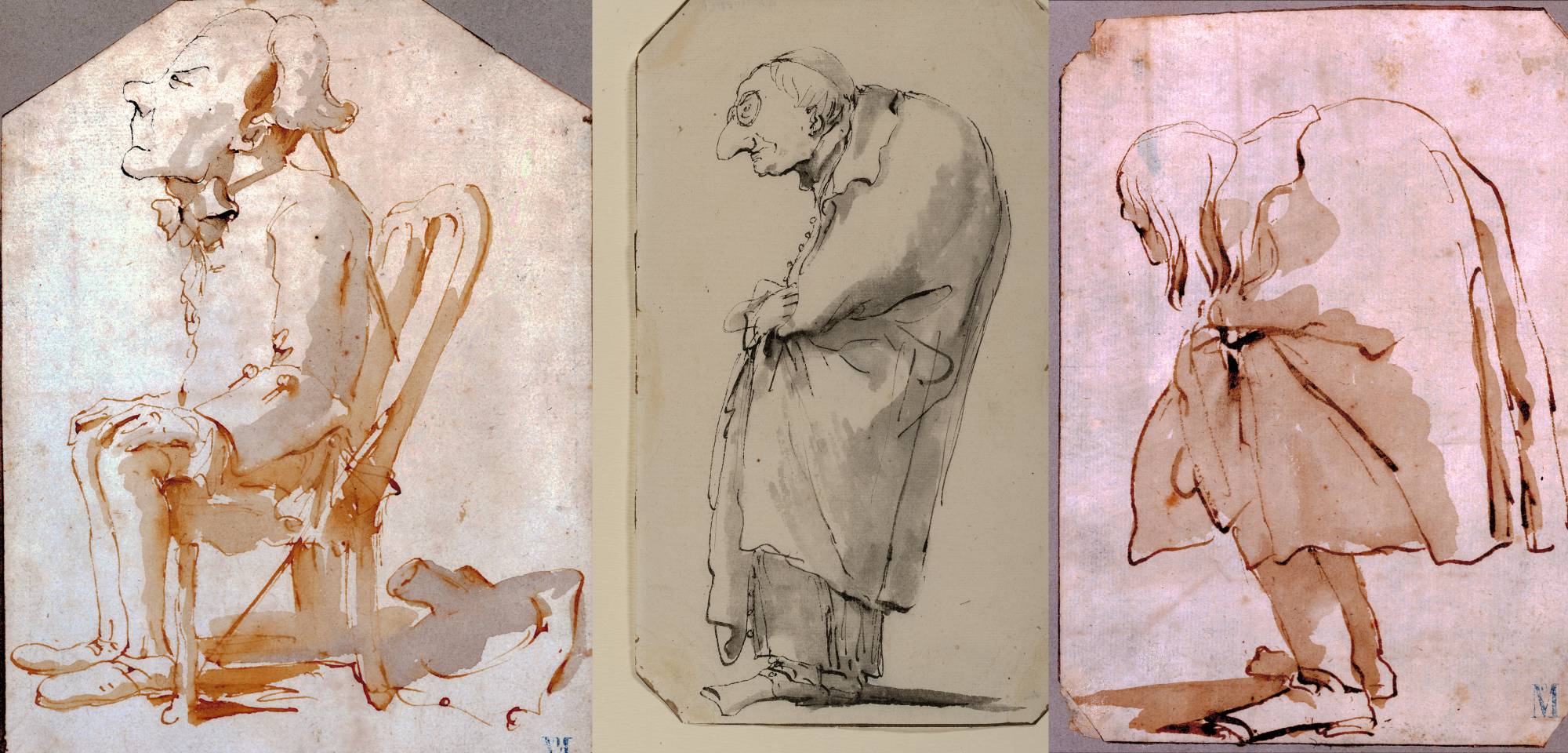

Our exhibition presents the effects this art current had especially in eighteenth-century Venice, highlighting Leonardo’s influence in the substrate of Venetian culture. An erudite, and amateur artist, such as Anton Maria Zanetti read Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting, books by Giovan Paolo Lomazzo, Annibale Carracci, and perused Leonardo’s heads in Caylus’s collection. Giovan Battista Tiepolo owned some of Lomazzo’s grotesque drawings. Zanetti drew his own comparison between caricature and opera.

The exhibition

The core idea of our exhibition is to provide context for the caricatures of the Ligabue Collection by making comparisons and tracing lines with drawings belonging to other collections, and not to produce an excursus into caricature in general. I think the most interesting result is our comparison between Tiepolo’s caricature belonging to the collection and the ones, again by Tiepolo, that are part of the drawings collection at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan.

Leonardo’s Old Woman

The drawing is quite famous. It had been attributed to Leonardo by Luisa Cogliati Arano, and in our exhibition, it is placed alongside other autographed drawings by Leonardo that belong to the Ambrosiana Library in Milan and to the Duke of Devonshire’s collection in Chatsworth. This piece of art is of utmost importance in how it carries a number of features and motifs that we identify the artist with. While the face is hideous, the vanity of the veil and headdress look, in their lightness, like the very hand of Leonardo. It is assumed that the drawing had been retraced at a later time by an unknown artist.

The timeframe

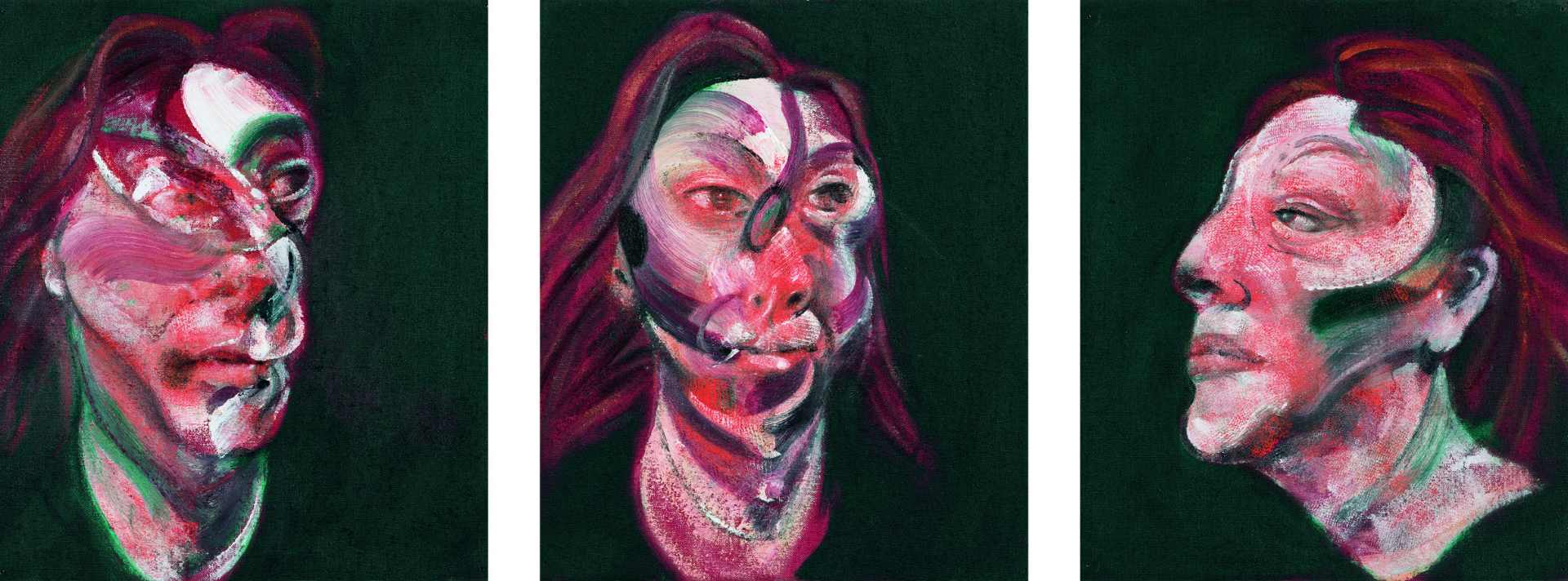

We started with Leonardo’s drawings dating to the late 1400s, and built upon them with pieces by some of his apprentice and disciples (Melzi, Giovanni Agostino da Lodi, Figino, Arcimboldo, Lomazzo). Further on, we have a sampling of naturalist art of Bolognese school (Annibale and Agostino Carracci, Donato Creti), and some examples from Central Italy and Northern Europe, on to the Venetian painters we mentioned earlier. Wrapping up the exhibition are prints and engravings from the late 1700s and early 1800s. the very last piece is a modern interpretation of the overall concept by none other than Francis Bacon, who explores the nightmare of the subconscious in the deformation of a woman’s facial features.