Director, artist, activist, founder of the International Institute of Political Murder, Milo Rau (Bern, 1975) is among the most awarded and well-known playwrights in the world and, of course, one of the most anticipated guests of this 50th Biennale Teatro, where he will stage his opera-manifesto La reprise. Histoire (s) du theatre.

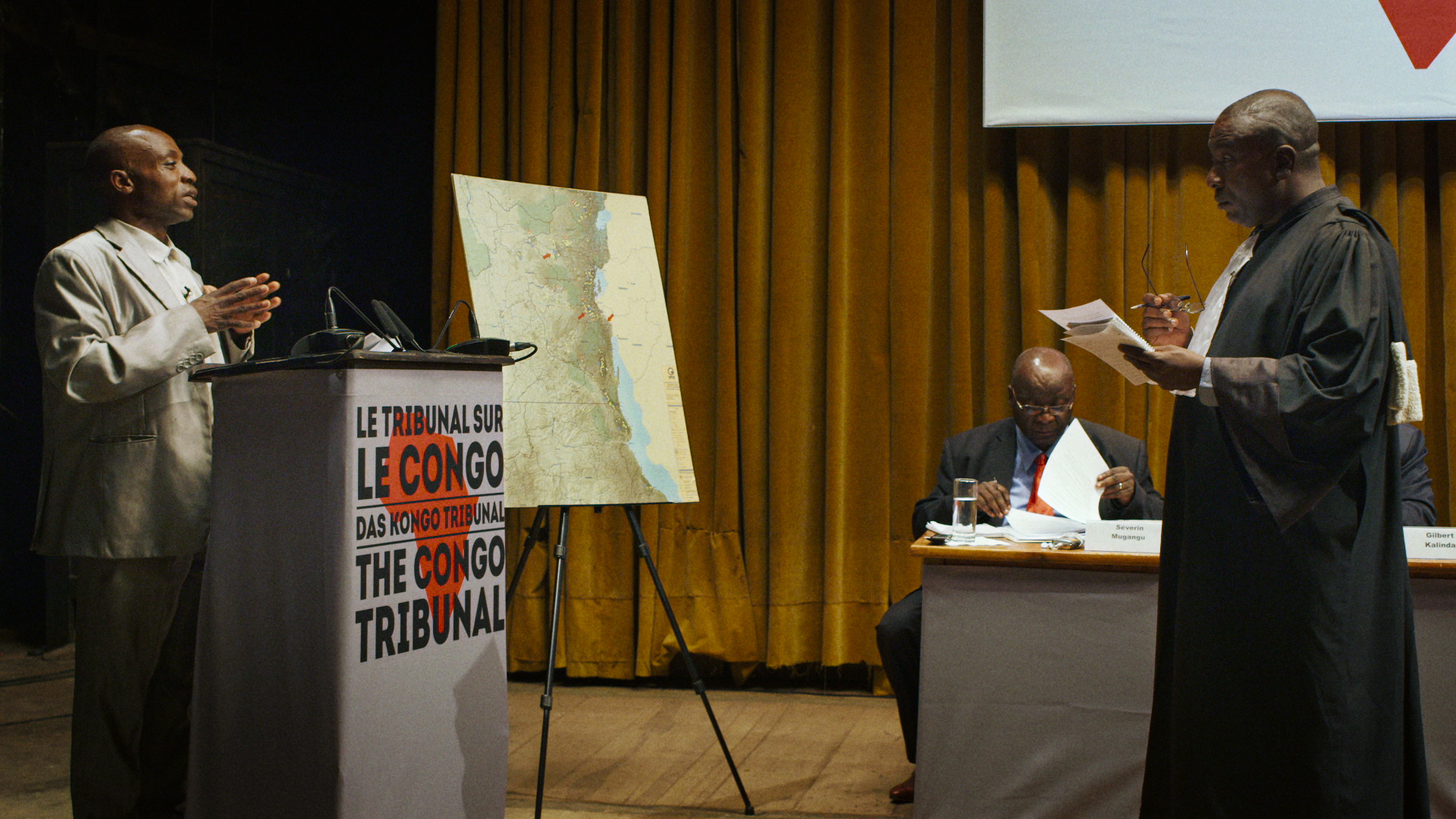

Director, artist, activist, founder of the International Institute of Political Murder, Milo Rau (Bern, 1975) is among the most awarded and well-known playwrights in the world and, of course, one of the most anticipated guests of this 50th Biennale Teatro, where he will stage his opera-manifesto La reprise. Histoire (s) du theatre. Palazzo Trevisan degli Ulivi will host a cinema exhibition dedicated to him Milo Rau: Actvism and Intimacy, a cycle of five films: Orestes in Mosul: The Making Of, The Congo Tribunal, Familie and The New Gospel. We had the pleasure of interviewing him shortly before his arrival in Venice.

Is violence inherent in man – and in theatre – and can cinema only represent just that, or can artists aspire to a proactive role?

There are many ways we can react or be proactive viz. war, disconnection, and the loss of God, or transcendence. This might be a reason, too. I think every play, every production, is the creation of an original, collective Republic – a collection of people that wouldn’t have existed otherwise, were it not for this project. I think we need more common projects, a common project for humanity, or at least for Europe. We have plenty of false gods: dictators, nationalism, the capital… what art can do is to represent the past and the possible future, show them under a different light. We want to see things we weren’t able to see when they happened, see them through the eyes of someone else, see the difference it makes when the same content is shown in different places. A book is never the same book everywhere: whether you stage it in Ukraine, in Iran, in Italy – it changes completely. There’s a lesson to be learned, there, and it is a very democratic lesson: no meaning is independent of the reader.

What about the continuous representation of violence? Wouldn’t that further engender violence?

I think the big question, here, is the ethical question of representation. Let’s take a step back: I think of physical violence as non-meaning. Making use of violence means taking away meaning and reducing a situation to a dialectic of domination and humiliation, or to death. What theatre can do is to recover the meaning in the act of representation, that’s why the play I will propose in Venice is called La reprise and not La répétition – it is a Kierkegaardian difference: to go back to the past to give a collective meaning to it in the act of representation. Representation and realistic art were born exactly to give meaning to life, to make it not forgotten, to make it tell a story. Art and stories have a cathartic function, they make a collective transgression possible, they make us realize we all have to die, and that violence dwells in our lives. It exists and it is represented in media. At the same time, we see elitist circles trying to create safe spaces and to exclude violence or to export it to the Third World, to the porn industry, and to put it out of elitist art. This is what we are searching for, the reason why we have a completely transgressive culture and economic system as a basis for this safe space. This is the contradiction we live in. So how can we create dialectics? How can we represent, in Kierkegaardian terms, that we have La reprise and not La répétition, in technical ways? How to overcome it? It’s a very Walter Benjaminesque question, too. We lost belief, that’s for sure. When I made this New Gospel film in Italy, a priest told me: Milo, the Bible is not a history book. The New Testament can only be put into practice; it is meaningless without its realization and belief. My act of belief is a form of re-enactment on a stage, today, using art. Or you could say, a ritual, a reprise of the quality, atmosphere, and meaning of some event “This is exactly why we have to represent violence”.

My act of belief is a form of re-enactment on a stage, today, using art. Or you could say, a ritual, a reprise of the quality, atmosphere, and meaning of some event “This is exactly why we have to represent violence”

I recently read Blok again. Do you think religion can play some relevant role in the future as well?

I think that religion or any kind of transcendence is the belief and true knowledge, even in extremely rational societies, that there is more meaning to it all than us existing only here, and then dying – gone forever. You could see in the pandemic: we were so afraid of dying, not only because we’d be gone, but because we knew that we would be gone forever. The possibility of death is the non-existence of everything we do. I think the act of belief, and again, the act of representation, of art and of any kind of ritual is trying to give eternity to the very moment and it only works – and that’s very important – in the collective. You may be confronted with somebody, or with nature, but there’s no ‘you’ alone in your head, that’s not possible.

I think this is really the big misunderstanding, the end of belief in the Protestant Reform in the 16th century: you can have a direct connection to God. I don’t think that this is possible. Only collectively can we create something that is like this relation to God. And I think this is the belief, the meaning of the Bible. The New Testament does not say: “if one of you is there, God exists”. It reads: “if two or three or four of you stand together, I’m in the midst of you”. Which means God only exists in the multiplication of the subject. That’s exactly what means to get together to do an act of art, for example. Whatever ritual, a demonstration, an act of love, schooling… without this belief, the belief that togetherness creates sense and loneliness destroys sense, will be losing its meaning. And I think an active meaning doesn’t exist, either.

I mean, when you go back in history you have Alexander Blok, of course, but then you can go further back and arrive to Structuralism. Structuralists say language, life, time – everything exists independently from us. I mean, I don’t know if the transcendence of meaning is a material fact. And I think the belief that transcendence is not existing is a rational misunderstanding of the last few hundred years, but it’s really a kind of apocalyptic belief that everything would end when you die. Because I mean, who cares when you die or when I die? Everything we did collectively remains there. You could say that, because I’m Marxist, I’m a believer. And I think you have to be a Marxist and to be a structuralist too to be able to believe. Karl Marx himself predicted it: the bourgeois society will do away with belief because capitalism doesn’t need it. People will come together in the marketplace, but not in any other form. The danger of missing belief is that another, different belief can invade society and be used as a propaganda tool. We are seeing this happening now with Russia. The absence of belief is a danger, not the fact that belief is not there anymore.

Is criticism in art a value in itself, rewarded by society and institutions?

The times of criticism and of institutional criticism and of the strategy of the bourgeois are over. For sixty years we said: we’ll include this minority, we’ll include this criticism. In State and Revolution, written before WWI, Lenin wrote that the moment they would build a monument for the revolutionary, the revolution would be over. I think our whole cultural industry is a factory of statues for criticism. We produce statues of criticism. I think this whole circle, this whole machine, is coming to an end. To pick an example from my life, when you look at the general assembly we created, The Congo Trials we created, The Moscow Trials we create, we created all these kinds of new institutions. We created them because they don’t exist. I don’t see any meaning to, for example, criticize Putin’s regime. I only see a meaning to construct an institution like a tribunal against Putin that has the power of being a tribunal and the legal basis to then create a new reality. And this is the lesson of late capitalism which is ultra-inclusive and would include, as you say, transgression and criticism inside its own functioning.

Berlin, Avignon, Brussels, Venice – theatre festivals to show innovative works. Are festival freer than regular theatres?

The big difference is that you also have theatres that function like festivals. I mean, if you were to make a difference, you would say, festivals are limited in time, invite, and coproduce. Theatres are open the all year round and produce. So, you have the danger of production, of course: you invest and you hope to earn on your investment. And at the same time, you have to do it the whole year. Everybody knows the reason why all these festivals are in spring and summer, it’s because then the theatres are not really working. With me leading an institution now, I learned the difference. When you have a team of a hundred people, with technicians, producers… you have to think in terms of one year, two years, three years, four years… so you have a different energy. That makes you, in a collective way, less free than you would be when you are just a curator. There’s a limitation inherent in a long timeframe and energy. You then understand how everything is connected to each other, and also very disconnected over a year. Also, a house can create an audience that comes to see things just because it happens in the house because they’re the public of this very house. You connect people to a house and then you can present whatever work. And that’s what you can do. I think humanity has an extreme dream tendency to get similar. So sometimes I think a festival in Brussels and a festival in Berlin are more similar than two theatres in Berlin

What is the role of the dramaturg then?

I think it depends on what approach you have. I mean, if you stage Chekhov, I think the role of the dramaturg is zero. And by the way, if you have good actors, also, the director is not needed. For me, the idea of the author and of the collective author that you would’ve described in the Ghent manifesto, is a completely empty stage, an empty page… You don’t know what you want to do. Then the role of the actor, director and dramaturg becomes important. Then, every actor and every director are not a professional anymore, they are responsible for everything, for the narration, for the form. And then we all become dramaturgs. The word Dramaturg has a meaning. It was introduced, I think, by Bertolt Brecht in German theater, and then it was finally used by Joseph Göbbels during the war. He said, “I’m the highest dramaturg of Germany, of German art”. He understood, of course, the role of the dramaturg.

One last question. You meet a friend on the street, and you have just two minutes. He asks you: “What are you going to present in Venice?”

I think I will present my methodology, because I bring La reprise, which is a basic work of how my method functions. The question of transcendence, of violence, of realism, everything is in. I bring professions, non-professions, different languages. It can be viewed as the stage translation of the Ghent manifesto. I bring The New Gospel and three other films: Family, The Congo Tribunal, and Oreste in Mosul. These films are also methodological films of different kind and are used to describe and change society. On top of it, I will run workshops about the only important question: how to represent reality and especially, the darkest sides of reality, which means violence in the arts.