La Tana was the final destination of the Black Sea trade route, the mud that the Venetian fleet traveled between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, leaving from the lagoon city in early spring to return in late autumn

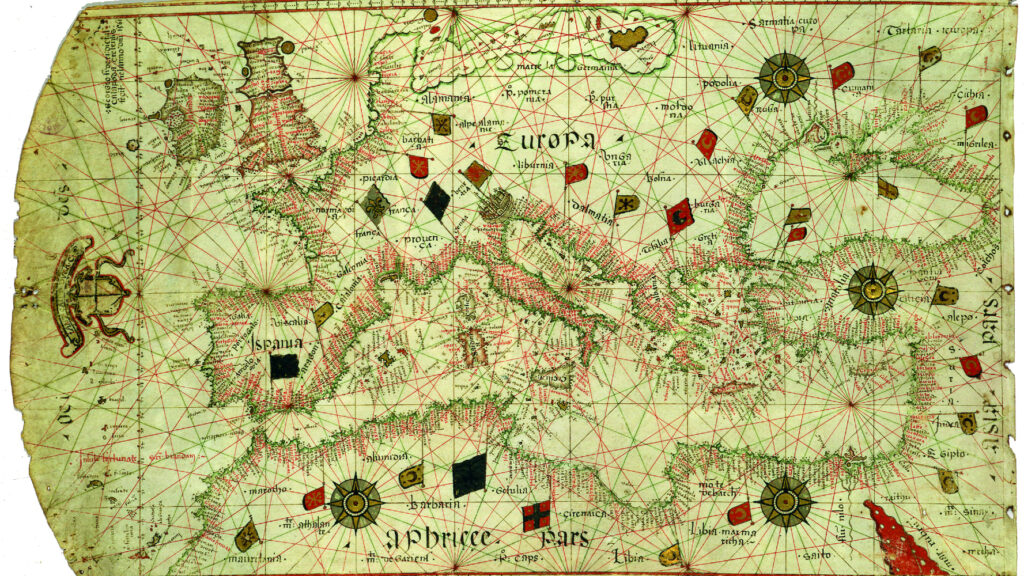

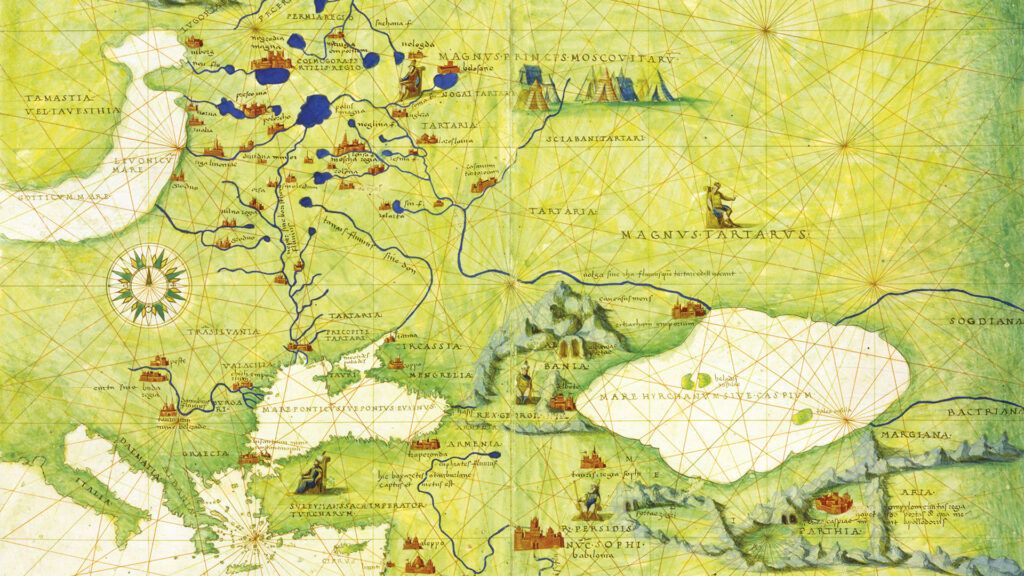

You enter the Corderie section of the Biennale through Campo della Tana. The name Tana is the Venetian rendition of a settlement on the eastern coast of the Azov Sea, at the mouth of the Don River, in the Russian marshlands some eighty kilometres from the Ukrainian Donbass (June 2022). The ancient chart of the Mediterranean, Black Sea, and Azov Sea by Giorgio Sideri, dating back to the sixteenth century and now preserved at Museo Correr, shows where it is (fig. 1). The town is also marked in an illuminated page of Battista Agnese’s Atlante of c. 1550 (preserved at the Library at Museo Correr), together with the vast Russian and Tatar plains (fig. 2).

Tana was important because it was the final destination of the Black Sea commercial route, which the Venetian merchant fleet would follow in the 1300s and 1400s, spring to late fall. In this port, Venetians maintained agents and warehouses, and each year, Venice would send at least two galleys, chartered to private merchants, loaded with silver and other precious and ready to sail back to Venice with a load of hides, dried fish, and hemp to make cordage.

In the mid-1400s, though, the route was interrupted. The Ottoman’s conquest of Constantinople, in 1455, severed the Venetians’ access to the Black Sea. The port of Trebizond, another important Venetian outpost, was taken by the Turks in 1461, which put a stop to Venice’s commerce with the Russian East and Tartary. In preparation for such an event, the Caxa del Canevo had been established at the Arsenale in 1303 to support the rising need of cordage for the big ships and their sails (narrow ships were the oar-powered ones). The Caxa was a provision office that looked for materials elsewhere: mainly in the countryside around the Italian cities of Bologna and Ferrara, and further inland. The need to cover all requirements for the large Venetian fleet prompted the Venetian government to sponsor first, and force later, a monopoly of hemp farming in the Venetia, with was to be centred around the cities of Este, Montagnana, and Cologna.

In 1579, in the area where Caxa del Canevo operated, the new Corderie (cordage mill) were built under a project by architect Antonio Da Ponte, who also designed the Rialto Bridge (1587) and the Prigioni Nuove (1589). The Corderie were 21 metres large, divided in three naves whose frames were supported by 84 large pillars, and 316 metres long by the Rio della Tana. This allowed long lines to be spun. A peculiar entryway made the Corderie independent of the Arsenale. The workforce was under the supervision of three officers appointed by the government, who took responsibility for the final quality of the product.

The hemp arrived in bales and was initially carded, both to clean it and to comb the fibres. It was later spun and spooled. A wheel, taking place at one end of the Corderie, twisted the strains and assembled them into ropes as they passed through grooves. A cart loaded with heavy stones kept the rope tight. Whereas heavier, stronger ropes were needed, the operation was repeated and bigger and bigger ropes were twined together.

The fate of the Corderie followed that of the Arsenale and, more in general, that of Venice. When the Venetian Republic came to an end, the French first, and the Austrian second, tried to acquire the know-how and the equipment of what was a large factory and a model for international shipbuilding.

A small print (fig. 3) dated 1833 and made for the appreciation of the Grand Tour travellers, is a rare, maybe unique depiction of still-operating Corderie, an image that would have been impossible to make at the times of the Venetian Republic, when information about shipbuilding and related activities was classified. Over time, the Corderie ceased operation and the large warehouse was partitioned for stability purposes, all the while impeding the appreciation of its full perspective. The building lied in this state until 1980, when it was chosen as exhibition area for the upcoming First Venice Architecture Biennale. In 1983, it was thoroughly renovated under the eye of the Superintendency for Fine Arts. The Corderie now display fully their original structure and historical charm.

The ancient craft of ropemaking is not all dead in Venice. In Giudecca, a small ropemaking business belonging to the Inio family was acquired by the City in 1955 and the equipment is now stored at the Arsenale, waiting to be refurbished.