While we anticipate how Architecture Biennale curator Lesley Lokko will lay out her Laboratory of the Future, we will share with you some reflections inspired by two essays on the modern city, which are essential to understand Lokko’s project.

Lesley Lokko (Ghana/Scotland) is an architect and teacher as well as best-selling author on the themes of race, identity, and of course architecture. She is the curator of the upcoming 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, which sets out to be the world stage for emerging talents, unique opportunities, and particular responsibility. The sense of this opportunity/responsibility lies all in the title of the exhibition itself: The Laboratory of the Future.

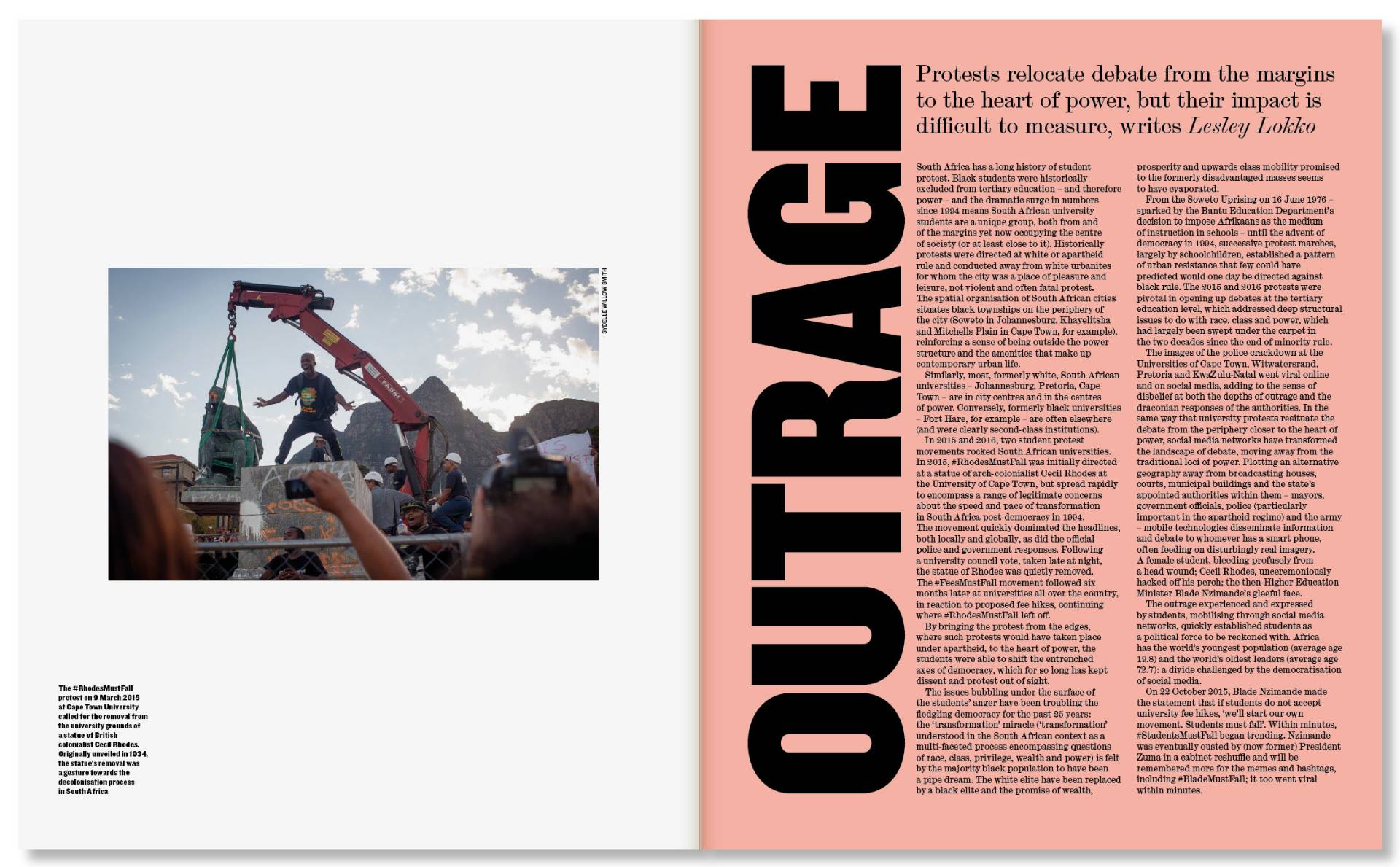

The content Lesley Lokko promised to focus on are new visions: “Today we can see the world in a way we never could. New technologies come and go all the time, and offer unfiltered views into life in parts of the world we would probably never visit, much less understand. To see what is close to us and what is far from us at the same time is also a sort of ‘double conscience’, the internal conflict of all who have been subjugated and colonized and that describes the vast majority of the world – not only the places ‘down there’, the poor countries, but also ‘up here’, in the metropolises and landscape of the global North.” There’s much talk of minorities and diversity in Europe, but the point of the matter is the minorities in the West are the majority, globally. Diversity in Africa is the norm. If there’s one place where all issues of equity, resources, race, hope, and fear converge, that would be Africa, the youngest continent. Europe is now questioning the origins, the identities, and the languages that many parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia never saw disappearing. This is a reversed perspective, though not a divisive one, because, says Lokko, on an anthropological level “we are all Africans, and what happens in Africa happens to all of us.” Consequently, the project is a recognition of architecture as a discipline of transformation and translation. From this continuous journey of codes and spaces, “from this ease of translation and this elasticity, we can learn.” “More than buildings, shapes, materials, or structures, the most precious and powerful gift of architecture is its ability to influence our way to see the world. The slow, careful translation of ideas into material form – and, all the more often, digital form – requires an almost constant change in our vision, restricting and widening at the same time our point of view to adapt to different scales, contexts, cultures, aspirations, as well to the many different needs that must be met to bring both buildings and knowledge to the world.”

For what will be the first post-pandemic edition of the Architecture Biennale, the focus will be as follows: “to revolutionize what we thought we knew on the dogmas and paradigms of architecture to give it a proper role in the building of the morrow.” To receive such a strong message of opportunity and responsibility, so strongly dedicated to the city of Venice, is such a privilege for us who are passioned about cities and architecture. “Every time I visit Venice, I think how strongly architecture fought to be here, how hard it battled gravity and logic. Venice presents itself as illogical, and that is why it is the perfect place to run a Biennale that looks forward to the future. This place will inspire us to open to what is new, and shows us that a different way to live and build is possible, and has been in the past. Also, it is exposed to the effects of climate change: Venice is our barometer.”

For what will be the first post-pandemic edition of the Architecture Biennale, the focus will be as follows: “to revolutionize what we thought we knew on the dogmas and paradigms of architecture to give it a proper role in the building of the morrow.” To receive such a strong message of opportunity and responsibility, so strongly dedicated to the city of Venice, is such a privilege for us who are passioned about cities and architecture. “Every time I visit Venice, I think how strongly architecture fought to be here, how hard it battled gravity and logic. Venice presents itself as illogical, and that is why it is the perfect place to run a Biennale that looks forward to the future. This place will inspire us to open to what is new, and shows us that a different way to live and build is possible, and has been in the past. Also, it is exposed to the effects of climate change: Venice is our barometer.”

As we wait to see how Lesley Lokko will lay out her Laboratory and who will be the protagonists of the international debate on the design of the future, we would like to share with you some reflections inspired by two recent readings on the modern city, which are essential to understand Lokko’s project.

Our first reflection has been inspired by the Texts on the (no longer) city. “The city does not exist anymore. Since the idea of the city has been twisted and expanded as never before, any insisting on a primordial concept of city – in visual, normative, building terms – always ends up, thanks to nostalgia – into irrelevance. Atlanta, Singapore, Dubai, Paris, Lille, Berlin, Tokyo, New York, Rotterdam, Moscow, London… the modern metropolis, with its uneven, unbridled development, with its apparently anarchical urbanism, disturbs us and questions our deepest values, or at least the most sentimental ones. How could such different architects, cultures (European, American, Asian), and political regimes arrive at configurations that look so similar? And why did “the triumph of the city coincide with a lack of reflection on the city itself”?

It is the decline of the West that goes hand in hand with the growth of non-western modernity, especially in Africa and Asia – according to Koolhaas. The idea of the city in these new modernity generated on political systems quite unlike our own, and quite different from the idea of civitas upon which we founded (what used to be) western civilization.

On Singapore, in particular, Koolhaas wrote The Generic City, a piece on the genesis of this city-state built on a blank slate – planned, thought out, and imposed from above. A key reading on the fate of the western city and on the emergence of a new kind of city liberated from the dependence on the city centre and the obsession of identity, a city where the public sphere abdicated, the triumph of awe-inspiring quiet. Urbanism, for Koolhaas, is again the crux of future architectural design, and this implies having a clear idea of what we’d want the world to be like.

The second reading is It’s All One Song by Marco Zanta, with text by Stefania Rössl. By observing the modern city with an extraordinary collection of photographs, it soon appears how the logic of urbanization is subject to short-sighted political strategies, unresponsive to the needs of quality of life. It seems to only abide by economic rules imposed from the top down, which take into little account the needs of places and people. Urban transformation that took place over the last twenty years are the main testimonies of expansion phenomena that, to address growing immigration, caused the homogenization of large swaths of built-up areas, mostly de-localized and concentrated in the city’s peripheries. Whole sections of the city appear decontextualized as well as bearing little respect for the place’s original character.

“The hypothesis that the world might be contained in a single large image – says Rössl – which is dear to Luigi Ghirri, reminds us that description of the Earth, as seen by the Moon, that had the ability to enclose all the images of the world. For that reason, in that tangled ‘hieroglyph of the real’, landscape represented, and may still represent, the beginning of a journey where real and imaginary dimensions can make new visions come to life.”

Cecilia Alemani and Lesley Lokko, creative research identity between Art and Architecture