Fully and essentially integrated into the Venice Film Festival, with special events and an own Competition with nominees of the highest quality, the Venice International Film Critics’ Week produces its 38th event with a diverse offer of modern cinema and stories that take the truest real life onto the silver screen.

The International Film Critics’ Week focuses on the kind of cinema that takes its own responsibility and strives for awareness in observation. How did you make your film picks for the 2023 edition?

Formal needs first. We are looking at original, powerful propositions. They won’t pass by unnoticed in any case, and they are great in gifting a valuable cinema experience. Aesthetical innovation, political standing, full awareness of the complexity of the present. We felt in touch with states of alienation, with the definition of (new) identities, with the relationship between people and surrounding space, and also with current issues like the marginalization in French banlieue, the ‘spider invasion’ as neo-capitalist threat, discrimination and abuse of intersexual people in sports.

Female presence is stronger than ever. We are waiting for a time when that won’t be even noticed anymore. What’s new on that front?

It is great news anyway, and it does mean that something is changing. The number of films submitted by female directors is growing fast, which means it is even easier for us to scout for quality. Women are not token participants anymore.

In our line-up, there is not particular feature that determines a ‘female point of view’—if that is a thing at all. I would rather speak of different sensitivities, but that applies to all films, it doesn’t matter the gender of the filmmaker. Le Vourdalak is a vampire story that, in a way, shows a possible end to the patriarchy, but has been made by a man, while Life Is Not a Competition, But I’m Winning has been made by a woman, moving forward into a queer vision that overcame the man/woman binary. Tana Gilbert’s look on the inmates in a female prison in Malqueridas hits close to home, and in About Last Year, the depiction of the bodies of three women by three female directors, which is central in the story, shows an affectionate, complicit point of view, never sexualized. This is one of the film’s strong suits. If it were made by a straight man, it might have looked different. Who knows?

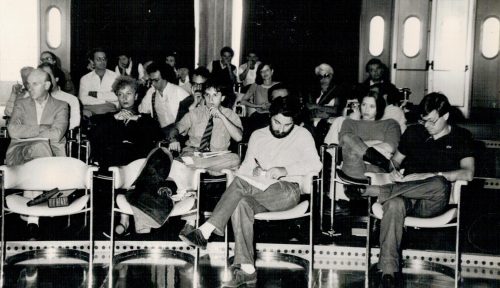

A documentary that challenges the idea and the definition of cinema by analysing testimonies and repertoire material from the 1960s to the present day. It is a study on the relationship between critics and authors in the history of Italian cinema.

...Documentary Passione Critica is the much-anticipated special event co-produced with the Biennale and the Venice Days programme.

Passione Critica is the brainchild of Cristiana Paternò. She created it to celebrate the fifty years of the National Italian Cinema Critics’ Guild. The film is a documentary that recollects memories and events that will allows to define our identity of critics of the present, while also initiate a conversation with some of the most important authors in Italian cinema. This comparison, occasionally a real

SIC@SIC is your short movie section, curated with Cinecittà since 2016. It proved very successful. This year, the section will open with Incontro di notte by Golden Lion-awarded Liliana Cavani and close with Grasshopper by Francesco Piras. Tell us more about these works.

In the year Liliana Cavani has been awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, we wanted to celebrate her with her directorial debut. It is an exercise she made in 1961, and it is also a very modern film about discrimination. In it, we see all the potential of a great filmmaker. We must realize that the short movie stage is crucial, and that a filmmaker’s talent, their spark, is visible early on. That’s what we do at SIC@SIC: we look for that spark.

Tilipirche (Sardinian language word for ‘grasshopper’, ed.) takes us back to the present. It is a ‘western’, sort of, a rough, hard-edged story set in a dry, thirsty countryside that reminds us of the climate challenge. Francesco Piras shot his film in the small Sardinian village of Noragugume in the tragic days of a grasshopper invasion that brought farmers to their knees.