For years, Céline Rouzet has collaborated with Radio France and realized investigative reportages (The Pulitzer Center, Le Monde diplomatique, The Huffington Post) in which she questioned people on the margins about integration issues, telling their stories: the hope of a disabled boy who dreams of finding love, the loneliness of someone who loses everything, to the guilt of abstinent or repentant pedophiles. Telling the stories of the “invisible,” giving voice to people who struggle daily in the face of the relentless forces that act in and on them–this is what animates her.

What inspired you to make this film?

I was working on a documentary when I had a sudden family issue to deal with. I tried to work through it, and the only way forward that I did find was to turn it into fiction. The beauty of genre cinema is that other than creating that particular style, it sheds light on situations, it inspires feelings and emotions, it allows us to put some distance between reality and us. I was then able to take a step back from what was happening in my personal life.

Your protagonist, Philémon, suffers from vampirism. Is it a metaphor we are looking at?

Vampires are fragile monsters: their condition is invisible upon first sight, but once they’re discovered, everybody fears them. Vampirism is comparable to a rare disease or a form of depression, something that forces you to isolate and that can be as dangerous for others as it is for the person who suffers from it. My film is a bit of a case study: what would happen when a family with a vampire son moves into a calm, tranquil town? What I wanted to show is society pushing violence on those few who dare step outside pre-established norms. Philémon is an affectionate young man who tries to integrate with locals while hiding what makes him different. However, he ends up becoming that very monster that society sees in him. The challenge, in my film, is to show Philémon as an innocent monster. What I want to do is to highlight the importance of dialogue, of allowing people to express themselves, and not force them into hiding.

They do their best to keep up appearances, and they planned for every detail. When the Férals move to a small, placid French town, they set out to look like an amiable, wholesome family. Philémon Féral is a shy, sweet teenager who hides his strange disease with the help of ...

They do their best to keep up appearances, and they planned for every detail. When the Férals move to a small, placid French town, they set out to look like an amiable, wholesome family. Philémon Féral is a shy, sweet teenag...

Your choice of debuting actor Mathias Legout Hammond to play Philémon.

I still don’t know how he ended up as a prospective, but when we saw him play, it was obvious right away that he was who we were looking for. We saw sweetness and restrained rage in him. He acted with intensity, and above all, with the same tone we had in mind when we wrote his lines. Better than anyone else, Mathias understood Philémon, a vampire who dreams of becoming a man, but is forced by society to remain a monster. Thinking about it now, it seems we witnessed the fatal meeting between actor and role.

Why is the story set in the 1990s?

Those were my teenage years, and they were also years when people with some ‘anomaly’, like rare diseases, were much more isolated than they are today. There were no online social networks, there were no patients’ groups, nor the attention we see today. Having said that, the issue of the integration of people with disabilities is still very urgent. I also wanted to create a sort of time gap with the present day.

In one scene, we see Philémon in his room with a copy of André Brink’s A Dry White Season on his nightstand. Is there a meaning in this choice?

That book shocked me. It is about apartheid in South Africa. Even though racism isn’t the topic of the film, the film does touch on the issue of violence between dominating and dominated and of failure of coexistence. The same topic is also present on both my first documentary – neo-colonialism – and on the film I’m thinking of doing next..

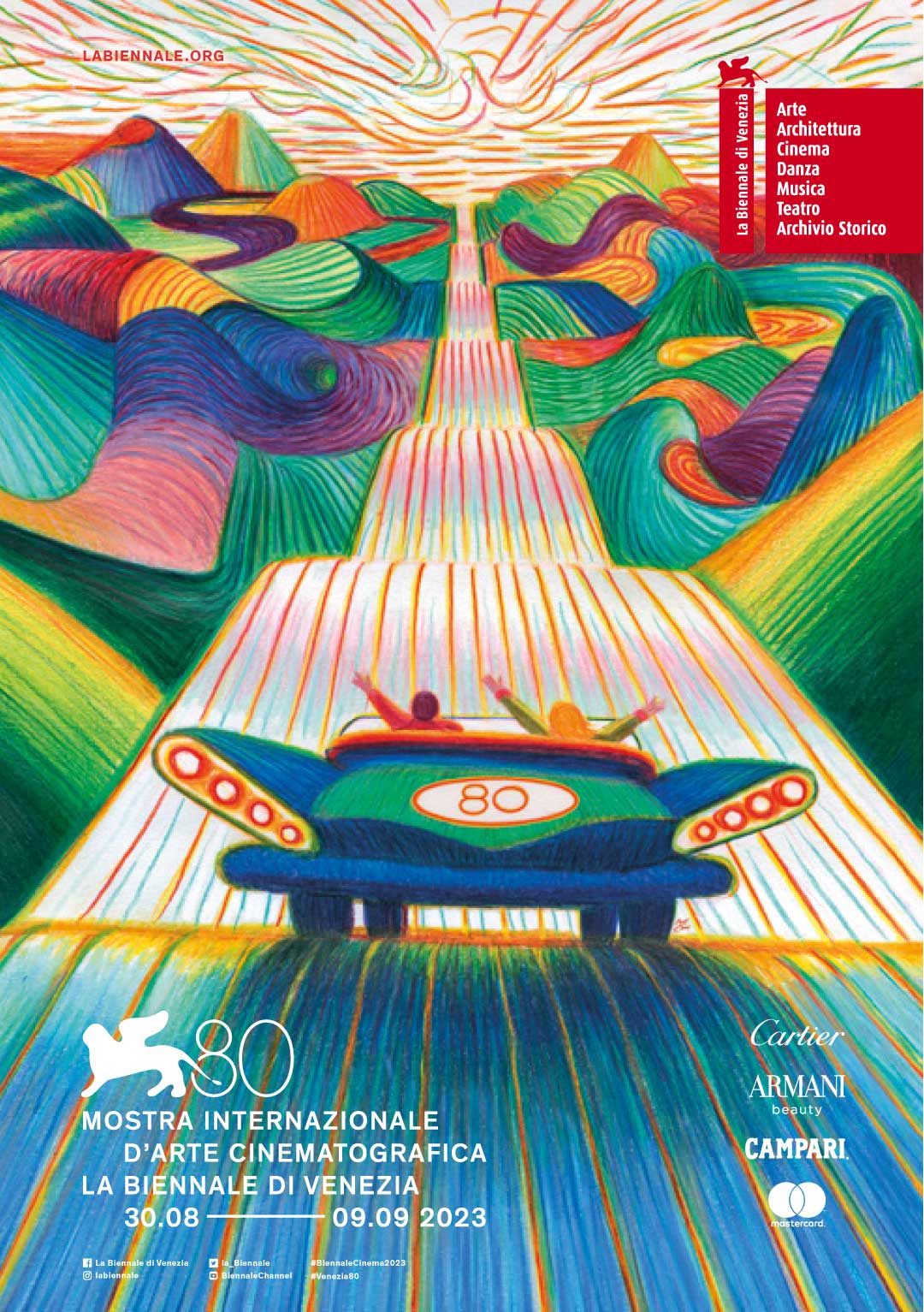

You will receive the Daily 2023, the official magazine of the 80 Venice Film Festival on a daily basis