Marco Petrus is the protagonist of the latest exhibition at Ca’ Pesaro – the International Modern Art Gallery of Venice. Capricci Veneziani, curated by Michele Bonuomo, is a collection of artworks inspired by the style of typical Venetian breeches once worn at the time of painters Vittore Carpaccio and Giovanni Mansueti (late 1400s-early 1500s).

Petrus’s art, and especially his vision, is very personal, emotional yet rigorous. The initial decisive, chiselled trait, likely a remnant of the artist’s education as an engraver, quickly evolves into a more rhythmic, architectural demeanour, on to a chiefly geometrical composition of clear lines, well-defined colour fields, and essentiality. On show at Ca’ Pesaro are twenty-six canvases arranged in a game of exchange, reference, and allusion that will involve the onlooker’s subjectivity and their instances of what is visible and what is lived.

Vittore Carpaccio as source of inspiration

Around the year 2015, I was working on a project for the city of Naples. I had done similar projects before: all had architecture as theme, though while in earlier cases I had used an itinerary as subject, in Naples’ case, I was going to focus on a single settlement, the Vele in Scampia, which reminded me of Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation at the Cité Radieuse in Marseille.

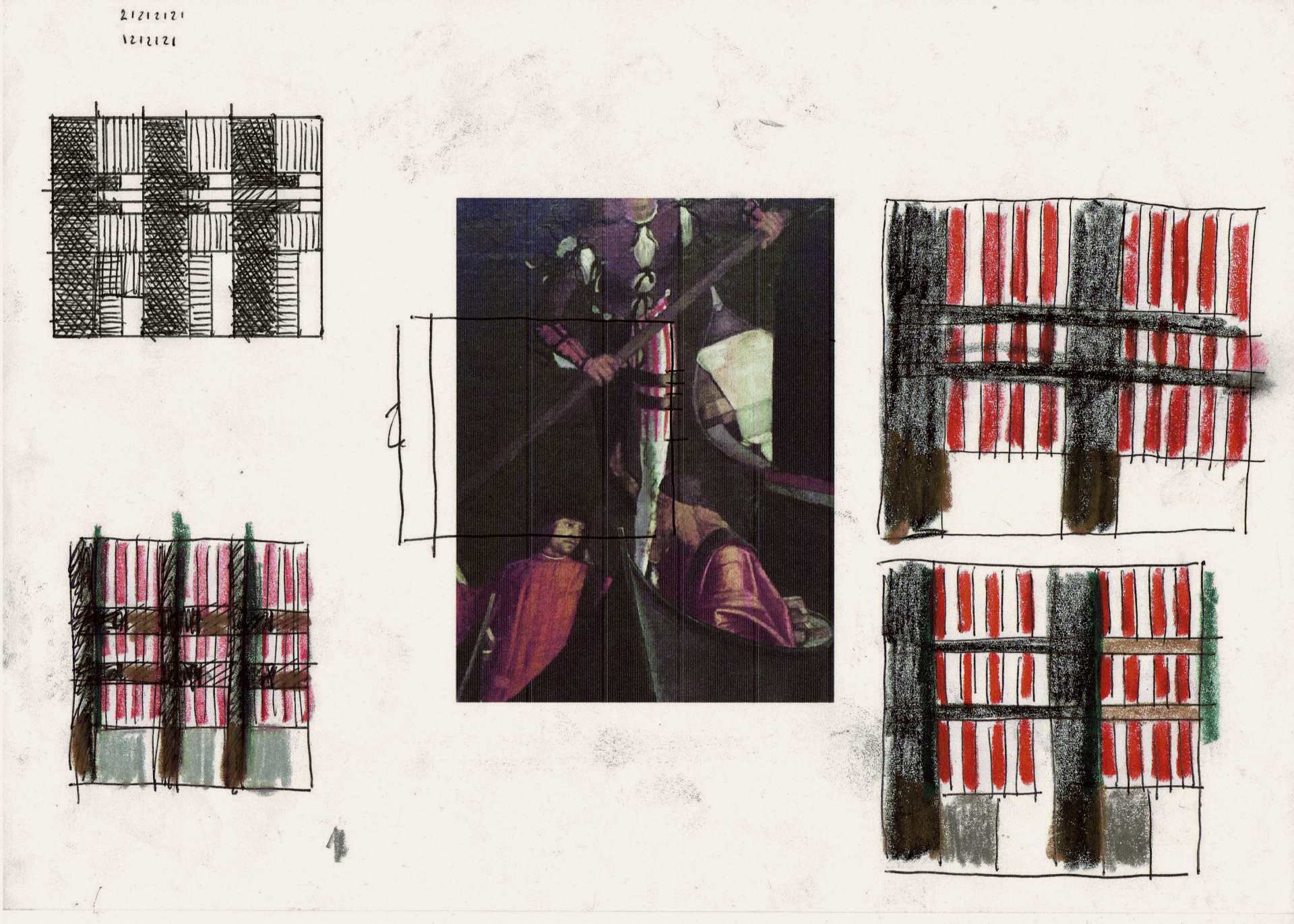

At the time, my exhibition at the Milan Triennale, Atlas, had just closed, and I wanted to expand my creative evolution. I wanted to develop my work on a higher level. The chance was brought to me by the fact that I had never seen the Vele in real life, and had to base my work on photographs and satellite imagery, which only tell half the story. Photographs depicted dilapidated structures, in ruins, and that’s not the message I had in mind at all. That’s when I decided my style, which was already stylized, was going to be pushed even more in that direction. I had wanted to make something similar to Matisse’s papiers découpés, construction paper collages, and found they paired perfectly with my paintings, where architecture was still recognizable, even though highly stylized. I assembled them in a sort of diptych, which is something I had never done before, to reinterpret the palette of the architecture by transpositioning the image outside the shape itself into a purely geometrical composition. That was my first venture into abstracticism. However, I didn’t want to go all-in, and kept the painting on the side – one larger, more architectural, and one smaller, more abstract. On to Carpaccio. While I knew his art from my frequent visits at the Accademia, my attention had never fallen onto some decorative details, such as the braghe, or breeches, worn in the paintings. I realized that can mean something, and that there was enough material to create a capriccio, whence the title of the exhibition, the fancy, or whim, to do something new and unexplored. My first ‘uniconic’ project after the Vele. I was curious as to how far I would have gone.

Your affinities with Carpaccio

In my intentions, there was no actual evocation of Carpaccio. The great maestros of the Venetian Renaissance have been the starting point to develop my own research. Specifically, I isolated, photographed, and studied Carpaccio’s canvases to recompose the style of the breeches under my own personal vision. Art is born of art, art begets inspiration. In my work, I have always followed my instincts. For me, painting is something conceptual, by which I mean, not representing of a concept, but following the concept of instinctive vision and emotion. I see houses, and I try to recompose them and make them my own, like Mariano Fortunyonce saw Carpaccio and tried to remake his cape, or Vittorio Zecchin re-creating vases inspired by Paolo Veronese, or Josef Albers who once took pictured of pyramids in Mexico and saw the abstract art in them.

How did this work in the art we will see at Ca’ Pesaro?

Whenever I work, I always strive to belong in the place my art will be exhibited at, so I try to adapt the art and create a unique project, a site-specific project, by all means. The largest paintings I made for this exhibition, which will be placed in the lower segments of the walls, have all been made in 2016. At the time, I still didn’t know where they will be exhibited, however, speaking with curator Michele Bonuomo, we thought about Venice. When I visited the museum, and the Dom Pérignon halls in particular, I realized how the tall walls therein were the perfect space for the large-sized paintings that were ready. The other part of the exhibition, where I display my smaller works, I prepared in 2019. Years passed, which allowed for further geometrical development. Other art I made – a mural painting for a private home in Milan, for example – influenced the 2019 series. These deviations and variations have been part of my creative itinerary and of everything that left its mark on my art. It might not be apparent, but it’s there.

How do you make art?

I rarely use sketches and colour swabs. I work directly on an actual-size painting, starting with an initial pencil outline. The paint is thin oil. I prefer flat colour washes. In the case of the art, we see at the current exhibition, I made tests with different proportions of the individual elements. Each element has been used in different pieces.

Your Venice

To me, Venice means coming back. I am fond of this city. My father Vitale Petrus (Kiev, 1934–Milan, 1984) studied at the Fine Arts Academy with Bruno Saetti, and participated in Milan’s art scene in the 1960s and 1970s. He was friends with Vittorio Basaglia and Cencio Eulisse, and he was acquainted with Alberto Gianquinto, Fabrizio Plessi, and Lucio Andrich, meaning he had a strong relationship with Venice. There are a few pieces of his at Ca’ Pesaro, in fact, as he won a number of awards at Bevilacqua La Masa. We lived in Venice for a couple years when I was an infant. My father died young, aged merely fifty, and I was still an architecture student. His friends helped me start my career as a printer, then engraver, and it took a while before I came to see myself as an artist. The path is now quite clear, though.