The founder of the architectural office UNA and of its alter ego UNLESS, Giulia Foscari tells us how urgent it is to regain possession of the ethical and political dimension of the architectural discipline.

She is an architect, but first, she is a citizen of Venice, a city that is unique in beauty and architecture, but is also fragile and sensitive. More than any other city, Venice endures in tangible fashion the environmental and climate crisis. A single example that, in some way, is the opposite of Antarctica, the seventh continent. Antarctica is as much fragile and contended, and global survival depends on it. Giulia Foscari traced the distance between Venice and Antarctica with questions, research, experience, solutions, and projects: work that is midway between professional practice and activism. Thanks to conscience, determination, and conviction, she will explain how urgent it is to reappropriate the ethical and political dimensions of architecture and participate to the building of a sustainable future.

Born in Venice, at the time the youngest member of the Order of Architects of Italy, founder of the architectural office UNA and its alter ego UNLESS, you worked in international architectural firms such as Zaha Hadid Architects, Foster & Partners and Rem Koolhaas’ OMA/AMO. What drew you to such profoundly different experiences? And which of these architects influenced you the most?

Curiosity. A deep desire to understand and learn how to observe what Buckminster Fuller called our “Spaceship Earth” from profoundly different perspectives, cultivating at all times a critical attitude that in my opinion is essential both to form an architectural thought and to inform any project. Amongst the architects you mentioned, with whom I had the privilege of working, unquestionably Rem Koolhaas has been, and still is, a very important reference for me.

Let’s start with UNLESS, a non-profit organisation that crosses the barriers of science and disciplines to represent a universal, shared knowledge on issues of global importance. What does UNLESS mean, and how does the result of your pilot project, Antarctic Resolution, now form the basis for real action to protect the Antarctic in particular, and global climate change more generally?

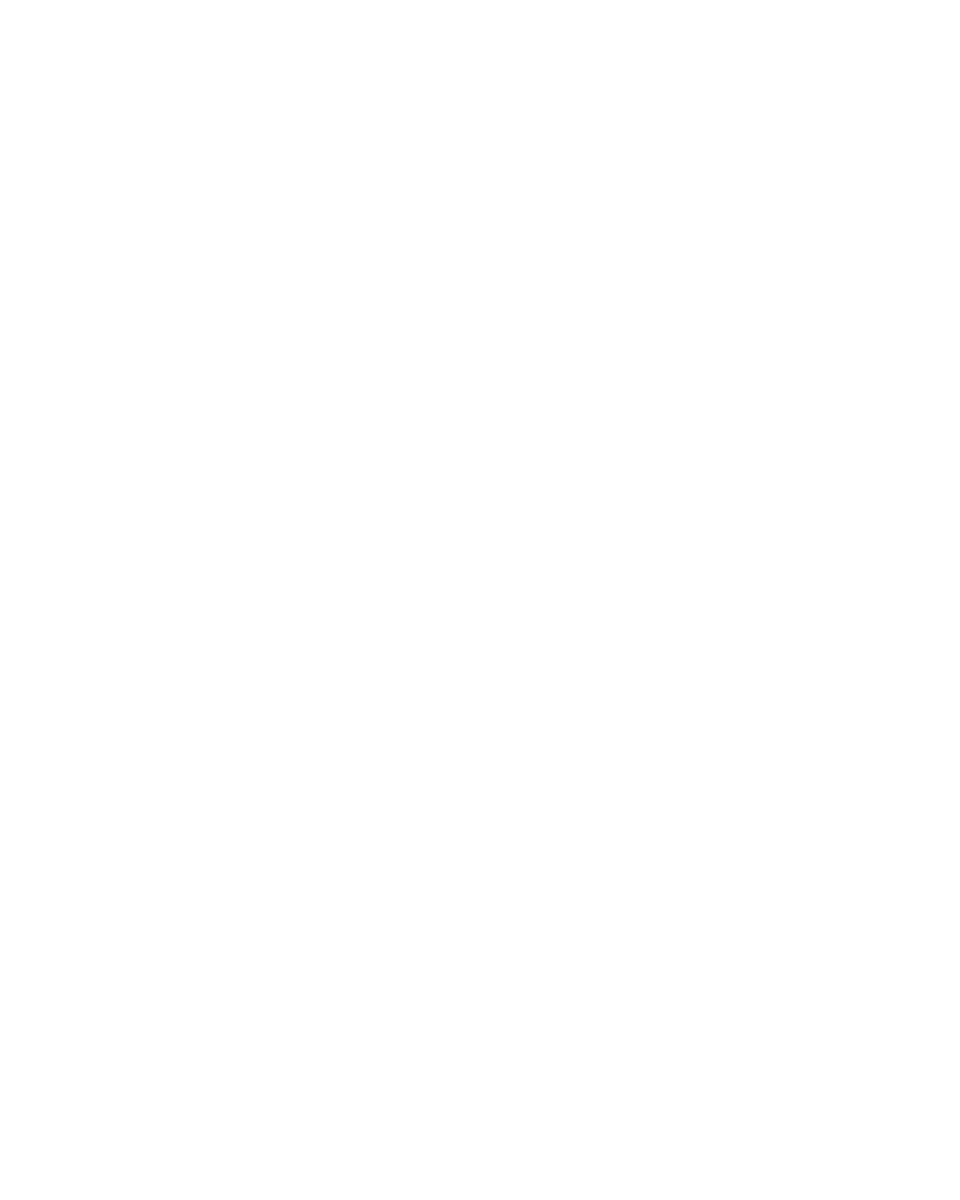

UNLESS is a term that conveys a sense of urgency: it invokes the need for immediate action to avert something severe from happening. At the same time, it is a term imbued with optimism, with the consciousness that action – individual and collective – has the potential to subvert our trajectory on “the highway to climate hell” (to quote the UN Secretary General’s opening statement at the recent COP27 assembly held in Sharm El Sheik). On the basis of this conviction, I founded UNLESS, an interdisciplinary “agency for change” in which, conscious that the industry in which we operate contributes to 40% of the global emissions, we embrace the social responsibilities of the architect in defence of inter-generational justice. The mission of UNLESS is to catalyse global attention to our Global Commons, namely extreme territories such as Antarctica, the Ocean, the Atmosphere and Space, which belong to humanity at large, but which, in absence of any indigenous population, have no constituency of their own that can demand the establishment of appropriate governance models to ensure their preservation. With our first project, Antarctic Resolution, we set out to highlight the “Antarctic problem” which is neglected by the collective consciousness, partly silenced by those who withhold the knowledge to fuel geopolitical interests, but which needs to be urgently addressed.

Research is a foundational element of your practice. It is a passion that led you to hold prestigious teaching positions both at the University of Hong Kong and the Architectural Association of London, and which has since led into the publication of important volumes, including Antarctic Resolution recently awarded also by the European Commission. What is the key message contained in the thousand pages of this book and how did the project evolve?

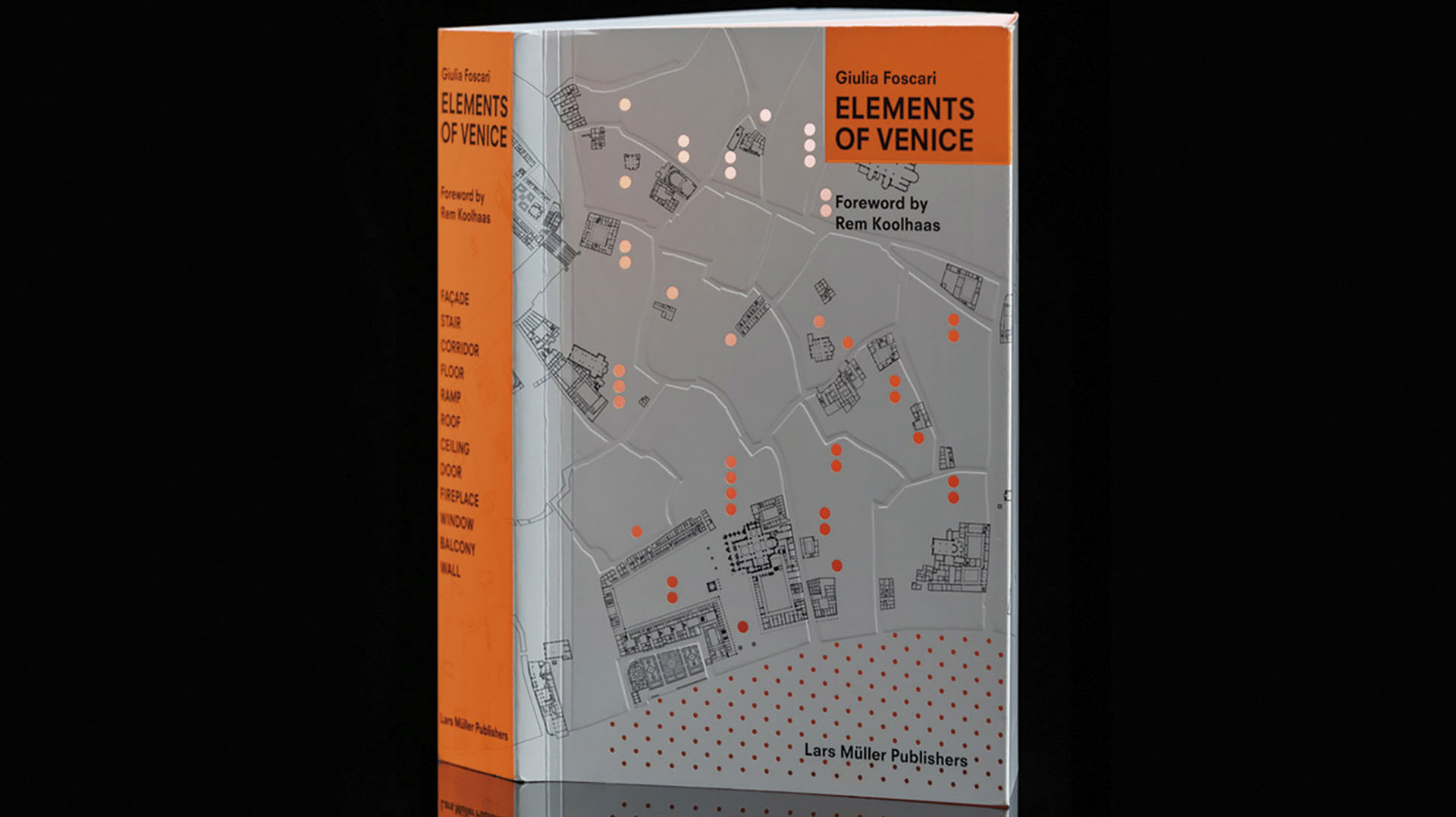

Antarctic Resolution is a book written by 150 multidisciplinary global experts, who collaborated in a collective effort to build a high-resolution picture of our seventh continent – a contested territory that accounts for 10% of the landmass of Planet Earth, 70% of its fresh water and 90% of its ice. The encyclopaedic volume emphasizes Antarctica’s role in the global ecosystem, highlighting its destructive potential (in the scenario in which the melting of its glaciers proceeds at the current rate, equal to the volume of 200 Olympic-size swimming pools per minute, threatening to submerge the world’s coastlines) and its constructive one, most evident if one considers that Antarctica represents the greatest archive of our planet’s climate history, offering scientific data that is essential to inform environmental policymaking. But Antarctic Resolution – newly accessible online on the homonymous Open Access platform that we launched to promote data democratization – does not “only” set out to produce and disseminate knowledge about Antarctica, but it should be understood as a “call to action”, in that it outlines imperative “Antarctic resolutions” that in my view are undeferrable.

Could you give us some examples of Antarctic resolutions?

Firstly, the need to promote a radical paradigm shift in the management of Antarctica that induces changes in the governance statutes of the continent, by imposing on the Member States of the Antarctic Treaty (signed in 1959) the obligation to share the outcomes of their scientific research and especially the data collected on the continent, into transnational Antarctic Data Center, accessible to scholars from around the world. I truly believe that in the poly-crisis condition we are experiencing, the definition of innovative transnational governance models for the Global Commons is a moral imperative that needs to be embraced for future generations. In the same spirit of global collaboration and sharing, I argue that it is urgent to define an actual masterplan for the continent that promotes the establishment of international scientific stations, halting once and for all the ongoing practice that encourages the proliferation of embassy-like station in support geopolitical ambitions to the detriment of science – the very science that is crucial to inform policies that can ensure the survival of human and non-human species on our planet.

How do you reconcile the work of UNA, the firm engaged in fulfilling public and private commissions, with the actions of UNLESS?

Well, on a personal level it is indeed quite intense, as both are totalizing realities to whom I would like to devote more time that what is realistically and physically possible. But I am an incurable optimist addicted to challenges, I feel strongly that both need to be pursued, and I manage to do this, it is thanks to the unwavering work of the fantastic team of colleagues with whom I have the great fortune to work, amongst whom I would like to mention Federica Zambeletti. On a conceptual level, although UNA and UNLESS are by nature two different organizations, they are intrinsically connected by the underlying conviction that there is an urgent need to reclaim the ethical and political dimension of the discipline of architecture in order to participate in the construction of a sustainable future. This implies, for UNA, a conscious choice to work primarily on preservation projects, and favour interventions – often radical ones – on the existing built heritage.

On radical interventions, you are project leader of the Anish Kapoor Foundation here in Venice. Could you tell us about the palace and the design ambitions of the project?

The palace chosen by Anish Kapoor as the home of the “Manfrin Project” is the result of a five-century metamorphic process. First conceived as a small-scale Gothic building, to which neighbouring volumes were progressively annexed, the palace was transformed during the 1700s by architect Andrea Tirali, who introduced two large voids (an unexpected double-height hall and a Roman-style courtyard) within the historic building and cladded its main front with a protorrationalist stone facade. This is how the palace appeared to the educated public of the renowned gallery of Girolamo Manfrin, before falling into collective oblivion through a rapid succession of owners and years of neglect. When we were called upon to design within these walls a laboratory for experimentation and art exhibitions for Anish, we decided to launch a new phase of this metamorphosis, one that would at the same time leaves ample evidence of the traces of decay in the palazzo’s history and introduces architectural innovations that reflect the particular exhibition needs, encouraging flexibility in programming. To this end, like Tirali, we worked by subtraction, removing all impediments included within the ground floor to create a permeability with the urban fabric that induces citizens to consider these spaces as qualifying elements of their everyday life, thus violating the hermetic nature with which the palace has presented itself to the city for centuries. In order to emphasize the porosity of the ground floor and to facilitate the access of large-scale artworks, we also introduced an autonomous gallery of unexpected proportions and strengthened the load-bearing capacity of the pavement, connecting this intervention to the construction of a system of protection from the so-called high waters that protects the building from floodings up to 2.10 meters above the mean sea level. Having achieved these initial goals, we designed an exhibition – in which we wanted to exalt the condition of “work in progress” – within the construction site itself on occasion of the Biennale Arte 2022; at present we are about to recommence the construction site and proceed with the works on the floors subsequent to the first.

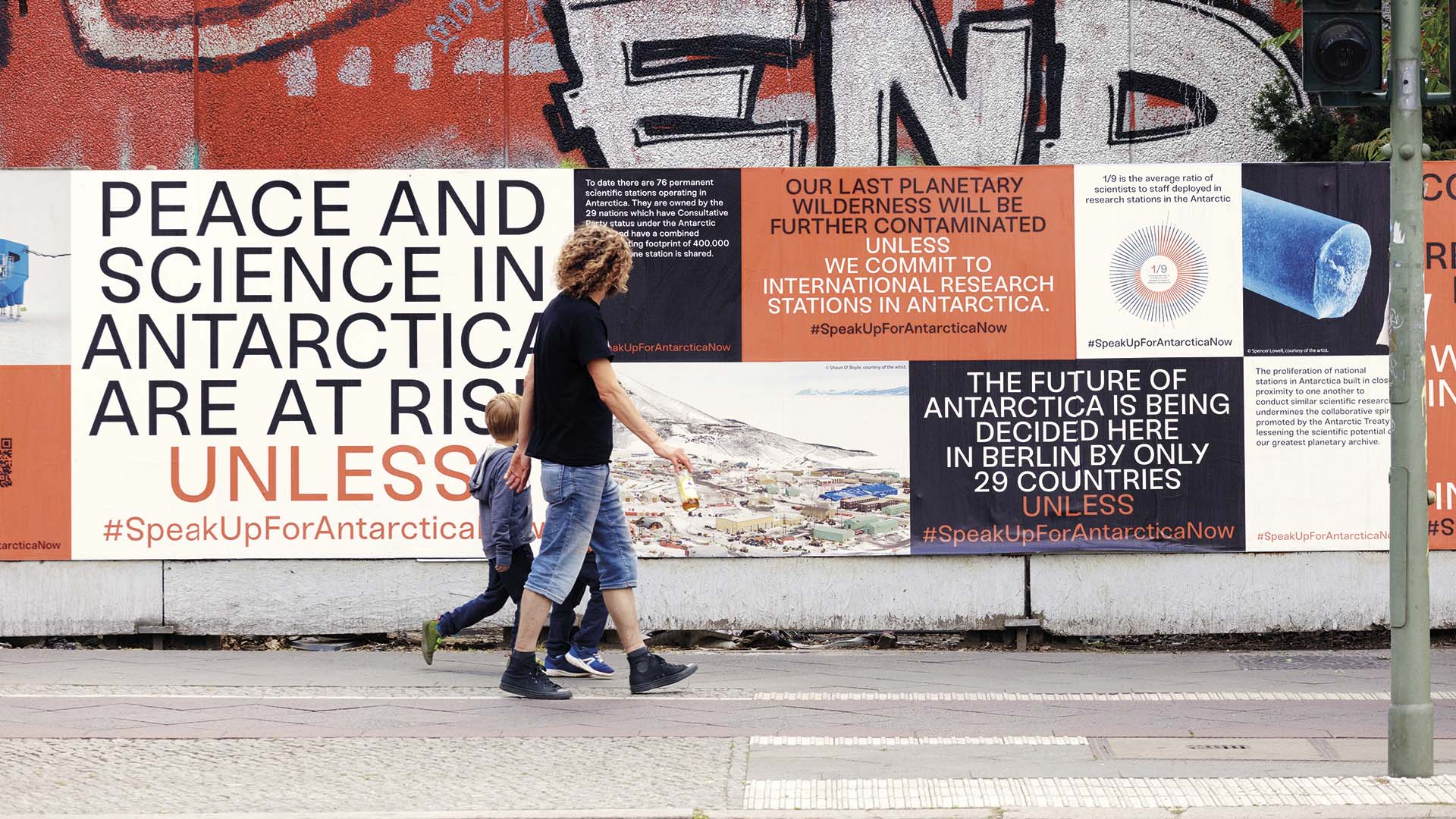

It is interesting that you talk about metamorphosis, considering that it is one of the recurring themes in Elements of Venice, the book you published in 2014, and which could be interpreted as the contemporary vision of John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice. How did the idea of this catalogue of fundamental elements of the city’s architecture come about, and what operational implications does it offer to the understanding of the city itself?

The idea of analysing independently the fundamental elements of architecture was launched by Rem Koolhaas, who dedicated the Central Pavilion of the 2014 Architecture Biennale to this theme. At the time I was living in Buenos Aires as I was responsible for the South American platform of OMA/AMO while working closely with Rem as a member of his curatorial team for the Biennale. In that context it seemed interesting to me to test his thesis at an urban scale, taking as a case study the city that hosted the Biennale itself: Venice. I confess that this idea was also informe by an intimate desire to finally study in a rigorous way the architecture of my hometown, from which I had moved away at age 17 to cultivate my independence. Elements of Venice was thus conceived in this context, but it soon revealed its potential in that it fostered a unique reading of the city, demonstrating how architectural elements and styles introduced in the Serenissima over the centuries were always a direct transposition, physical I would say, of political, ideological, and social shifts, and not just the result of formal decision as one might suspect. The research also revealed the metamorphic nature of the city of Venice, an avant-garde, liberal city that was a cultural epicentre for centuries, and whose urban and architectural form underwent profound transformations. An almost forensic, anatomical reading of Venice’s architecture not only allows to read the history of the republic on its stones – to reconnect to your reference of Ruskin – but above all it conveys (at least to me) a feeling of optimism that legitimizes contemporary architects to imagine a future for Venice that is beyond the image of a city-museum mostly associated with the lagoon city.

Your presence with a variety of projects at multiple editions of the Venice Architecture Biennials establishes your close connection with the Venetian institution. Is there a new presence or collaboration of yours in sight?

On the occasion of the upcoming Biennale curated by Lesley Lokko, I have been invited to contribute to a Collateral Event promoted by the New European Bauhaus (NEB). It is a two-day conference held at the IUAV University in the presence of Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission. In this context, I will contribute to the panel discussion The Global Commons and Climate Change: Venice reporting from the front and lead a Radical NEB Lab.

You just moved to Venice, with the whole team of UNA and UNLESS, after spending twenty-five years between London, Hong Kong, Buenos Aires, and Hamburg. Why did you decided to come back to your birth city? What role does Venice play in you existential and professional DNA? What is today your idea, your vision for a city at once entangled in its uniquely tourist dimension and the subject of a proflux of hypothetical redevelopment paper-projects?

Venice is unavoidable. If one has the fortune, as I had, to be born here and to have been educated to recognize within a painting, an architecture, or simply in a detail, the ideological, cultural and political thought of a republic that alone for centuries promoted and defended the values of justice, inclusion, freedom of speech and press that today we still sadly cannot take for granted, it is inevitable that at some point of one’s life, however nomadic one might be by nature, one feels the “call of the wild.” And the reference to Jack London’s text here is not coincidental because Venice’s uniqueness, and thus its catalytic power, is not traceable “only” to its millennia-old artifacts that embody essential ethical values, but also to its being inextricably entangled and compatible with nature, immersed as it is in the brackish waters of the lagoon since centuries. This inherent ability of Venice to coexist in the lagoon’s ecosystem without endangering its existence – with an approach that today can be found almost exclusively in indigenous settlements from which we can only learn – is something to reflect upon carefully. But this condition renders it as unique as vulnerable. Not unlike all other coastal areas of the world (from the Marshall Islands to cities like Jakarta), Venice’s future existence is threatened by anthropogenic climate change. But unlike other global coastal settlements that are in danger of being submerged by tens of meters of water (suffice it to say that a melting of Antarctica would lead to a rise in the global mean sea of 60 meters) Venice has an unparalleled media potential that we should absolutely mobilize. With this in mind, I believe that while we should certainly continue to invest (by means of strategies that include financial incentives) to attract cultural art foundations, Venice – the barometer of climate change par excellence – should become the world epicentre for studies on climate change by creating transnational infrastructures that catalyse here in the lagoon the best interdisciplinary minds in the field and global scientific data. A project of this nature, which when viewed from the European perspective is perfectly aligned with the ambitions expressed in the Green Deal, would allow Venice, historically the “Queen of the seas”, to once again be a world reference but no longer as a feared republic with aspirations of domination, rather as the “protector” of those same seas – now overheated, acidified, and with threatened biodiversity – and, the promoter of the preservation of our Blue Planet.

Featured image: L’architetto Giulia Foscari sotto la porta di Brandeburgo a Berlino durante la campagna di sensibilizzazione urbana Speak Up for Antarctica – Courtesy of UNLESS © Louis De Belle