81. Venice Film Festival

80. Venice Film Festival

79. Venice Film Festival

The Biennale Arte Guide

Foreigners Everywhere

The Biennale Architecture Guide

The Laboratory of the Future

The Biennale Arte Guide

Il latte dei sogni

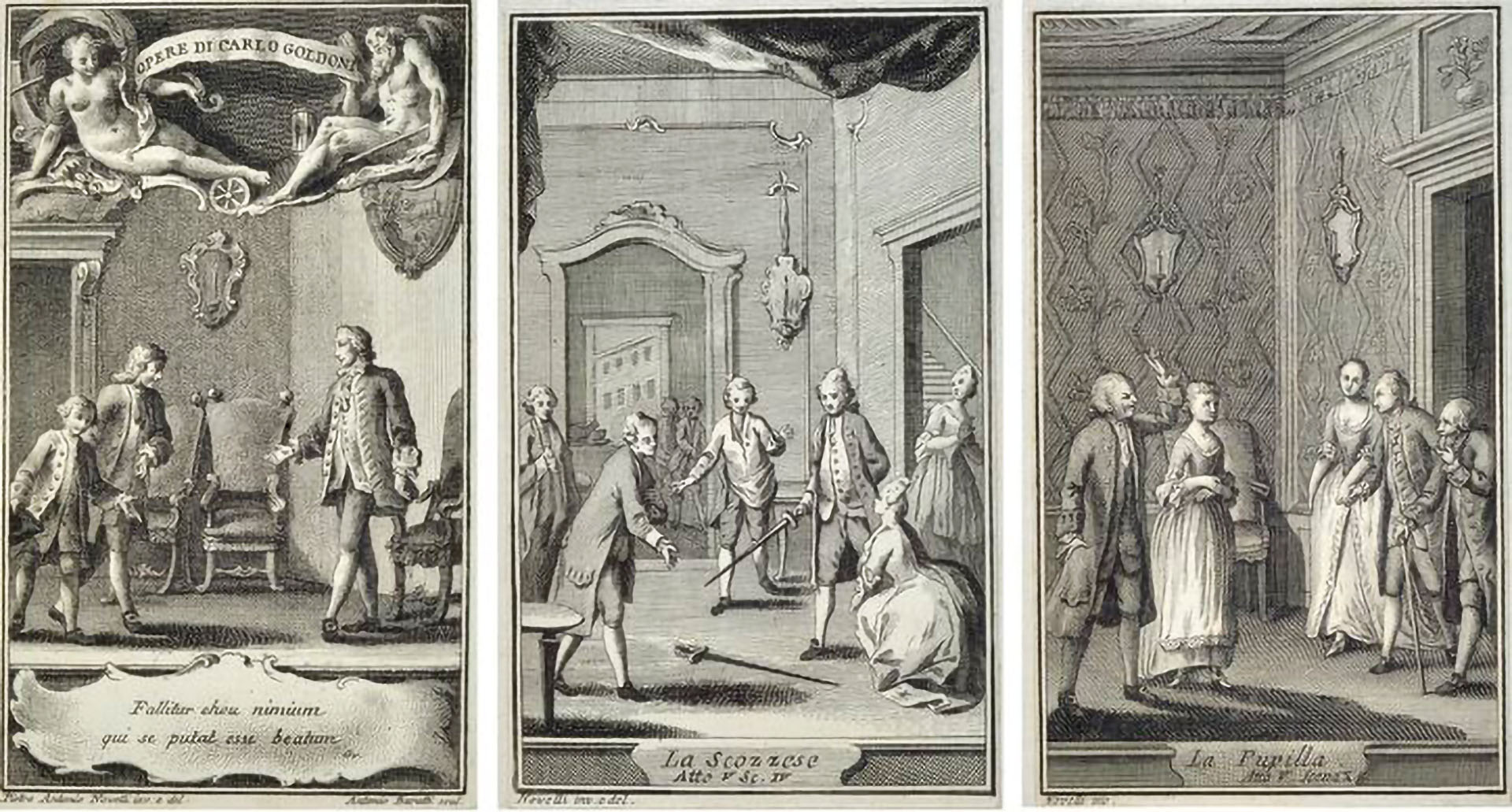

Giacomo Casanova and Carlo Goldoni both wrote their memoirs in French, died in poverty far from their homeland, and joined Freemasonry… A passionate investigator of the relationships between the key figures of the 18th century and Freemasonry, Alberto Fiorin takes us back three centuries to Rio Marin 803, the former seat of the Masonic Lodge of Venice.

Many interesting characters populated eighteenth-century Venice. Two of them, among the most famous, are apparently antithetical to one another: Giacomo Casanova, a man of a myriad interests and activities, though known especially as a libertine, and Carlo Goldoni, a reformer and innovator of theatre who lived with his wife Maria Nicoletta Connio until death. Yet, both Casanova and Goldoni were freemasons, wrote their memoirs in French, and died impoverished and in exile. For Casanova, a conservative who believed that the commons needed to remain ignorant for the nation to be at peace, adhering to Freemasonry was a way to enter high society and acquaint himself with magical, exoteric practices. Goldoni, on the other hand, was more interested in engaging with the climate of renewal that bourgeois morality was developing.

In Goldoni’s play The Coffee Shop, character Ridolfo states: “To be a good man, one needs to do more than refrain from stealing, he needs to do good deeds, too” – which shows the rectitude and common sense that the new man should internalize, opposite the corruption and decadence of the nobility, as in the Marriage of Figaro by Mozart, who, by the way, was also a Freemason. We know that Casanova was initiated in Lyon, France, in 1750 at a Lodge known as Amitié amis choisis. We don’t know as much about Goldoni: he was well acquainted with Alvise Pisani, a reknowned freemason and former ambassador to Spain, and Freemasonry historian Carlo Francovich maintains that he was initiated at the highest level. Whatever the case, the theme of friendship, which itself presumes parity beyond social class, connotates Goldoni’s plays and gives us a better sense of his opinions on the matter.

In The Servant of Two Masters (1745):

BEATRICE (disguised as a man, having invited Pantalone to have dinner at Brighella’s inn): There’s nothing one enjoys more than good wine in good company.

PANTALONE: Good company! Ah, if you had known them! That was good company! Good honest fellows, with many a good story to tell. God bless them. Seven or eight of them there were, and there wasn’t the like of them in all the world.

Seven Masters are needed, in fact, to start a Lodge. Earlier, in the same play, the danger of Freemasonry appears to be understated:

SILVIO: I heard just now that you had given your oath.

CLARICE: My oath does not bind me to marry him.

SILVIO: Then what did you swear?

CLARICE: Dear Silvio, have mercy on me; I cannot tell you.

SILVIO: Why not?

CLARICE: Because I am sworn to silence.

SILVIO: That proves your guilt.

CLARICE: No, I am innocent.

SILVIO: Innocent people have no secrets.

CLARICE: Indeed I should be guilty if I spoke.

It is in The Curious Women of 1753 that the Masonic Lodge is eventually staged, although disguised. Goldoni wrote as much in his memoir. Sure, the hall shows none of the characteristic features, but the checkerboard in the first scene reminds of flooring. Anyway, setting aside arcane, complex symbols, it really took little to be a freemason in the 1700s. What do these men do in the play? Their wives’ deductions offer a plethora of the different interpretations that had been given on the ‘masonic secret’, what freemasons actually do or discuss. Both in large and small affairs, secrecy, as it were, begs curiosity. When one doesn’t know, but wants to, that’s when the worst happens. Our curious women think of everything: gambling, consorting with other women, alchemy, treasure hunting. There’s no real answer, though, any guess is just as good as the next, and they end up all being wrong, anyway. At some point, Arlecchino – the women’s confidant – makes them all happy by indulging the supposition of each. “Tell everybody they’re right, and they’ll all be happy!”. What difference does it make, anyway? The secret, as Casanova once wrote, will always be there.

Only at the end does Pantalone tell newly-initiated Flaminio Malduri (F. M., free mason?) the fraternity’s Rules:

1. No one should be admitted who is not honest, civil, and pious.

2. Everyone may take pleasure in legitimate, honest, virtuous, exemplary activities.

3. Common luncheons are encouraged, provided they are conducted in sobriety and in moderation. He who indulges in drink and gets inebriated, will pay for the outing the first time, and be expelled the second.

4. Each will pledge one ecu for the upkeep of everything necessary: furniture, lighting, servants, books, paper, etc…

5. The introduction of women shall forever be proscribed, so that no scandal, or dissent, or jealousy shall take place.

6. Any leftover money shall be kept in deposit to help someone who is poor and in shame.

7. If any brother shall fall in disgrace, though with his reputation intact, the others shall assist him with brotherly love.

8. He who shall commit any crime or misdemeanour shall be expelled.

9. Ceremonies, compliments, affectation are proscribed. You want to leave, you leave; nothing in necessary other than friendship.

The curious women eventually scheme their way into the fraternity house and, once they heard the call for love, are convinced their husbands are indeed pious, and just for that once, they are allowed to stay for dinner. We understand these to be simple principles, not dissimilar in spirit to those that animate Venetian charities today, all unaffiliated, like the ancient societies they derive from. Now, these charities have nothing to do with Freemasonry, but like it, and like Goldoni’s club, honesty and charity are at the base of fraternities that do look very similar.