81. Venice Film Festival

80. Venice Film Festival

79. Venice Film Festival

The Biennale Arte Guide

Foreigners Everywhere

The Biennale Architecture Guide

The Laboratory of the Future

The Biennale Arte Guide

Il latte dei sogni

The history of lighting at Palazzo Ducale, from its first artificial lighting fixtures to the present day: a reflection looking forward to the World Day of Energy Saving and Sustainable Lifestyle, on February 16, 2023.

The frail timber framing that innervate Palazzo Ducale, the large canvases that cover its wall (on evidence: Francesco Guardi, Sala del Collegio, Louvre Museum), the papers and documents that Venetian bureaucrats produced continuously as they operated government and justice administration: all were prone to quickly bring about disaster if fire, used for lighting, cooking, and heating, were to escape control. The biggest threat resided in those halls that were the most used daily: from small votive candles to fireplaces (there are a mere eleven in the whole Palazzo) to the torches used by the Criminal Night Patrol (a real thing). Risk had to be managed and reduced to a minimum by concentrating work and celebrations during daylight.

In December 1821 – the days of the Venetian Republic now gone – the umpteenth fire threatened the actual existence of the building, which prompted Austrian Emperor Francis II (then ruling Venice) to order that the contents of the library and the sculpture collection be kept in different buildings, thus starting the epoch of the Palazzo Ducale as a kind of museum in and about itself. In 1857, Venetian intellectual and art lover Emmanuele Cicogna accompanied the new emperor, Franz Joseph, on a visit to the Palazzo. (The Emperor’s trip to Italy, Illustrirte Zeitung, 1857). Even then, there were visitors who shunned the artistic beauty of the Palazzo for a visit to the Prisons, where daylight would never shine in, fascinated by a darker history of Venice as a ruthless avenger and executioner (Francesco Galimberti, Francesco De Pian, First vault, where prisoners sentenced for treason are kept).

John Ruskin travelled to Venice to write his The Stones of Venice right after the revolutionary years of 1848-49, when the cruel Austrian rule relented, in front of a city whose spirit fizzled out, resigned. It is no surprise that Ruskin, in his passion for Gothic art, saw as a slap in the face the lighting apparatus that was installed in 1844. The installation used 144 lamps. (Luigi Querena, The first night of bombing on July 29, 1848 – Dionisio Moretti, Piazza San Marco / View on the portico at Palazzo Ducale, mid-1800s).

The lighting of Palazzo Ducale was the first attempt to give Venice some form of public illumination, at least in its most central district, at a time when it was becoming commonplace in all major European cities. At the time, visitors to Palazzo Ducale followed sunlight to get the best out of every hall. Henry James often visited Venice, and noted acute observations in a letter to his brother William of 1869: at Palazzo Ducale, everything looked so luminous and splendid to Henry, and he reckoned the Palazzo was the most beautiful thing to see in Venice, especially in the morning or early afternoon, around one, where there is much less of a crowd. Sunlight enters the large windows up from the water surface and shines on the walls and gilded ceilings.

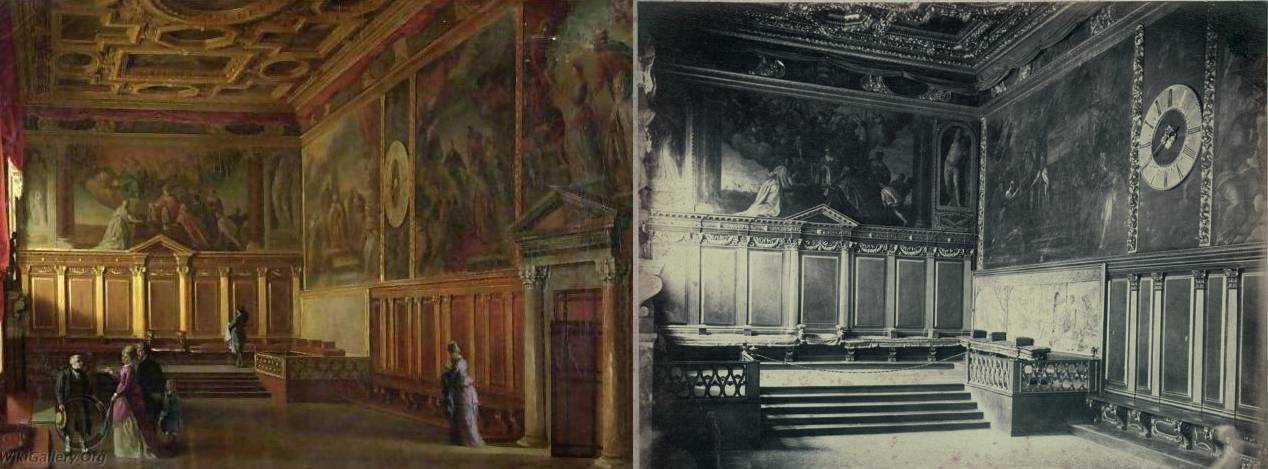

Over the same period, many artists would also visit the Palazzo and looked for the best light to portray its interiors. John Wharlton Bunney was in Venice between 1877 and 1882, and painted a morning sunshine-imbued Interior of the Sala del Senato (John Wharlton Bunney, Interior of the Sala del Senato, 1882, Sheffield City Art Galleries), while John Sargent left us a Sala del Maggior Consiglio of 1898 (Singer Sargent, Sala del Maggior Consiglio, 1898,private collection) where the warm early afternoon light bursts through the large windows and the balcony that overlooks the San Marco Basin, illuminating the gilded ceiling and art by Veronese. On the background, Tintoretto’s Paradise also shines under sunlight, disclaiming Tintoretto’s own fame as a ‘dark painter’ once acquired thanks to his work at Scuola Grande di San Rocco, which couldn’t enjoy lighting conditions as favourable as the ones at Palazzo.

Art photographers also began studying the secrets of light at Palazzo Ducale for their plates, which required exposure times not dissimilar from hand-painting. (Sala del Collegio in sunset light, albumen print, 1800s – Giovanni Battista Dalla Libera, Sala del Collegio at Palazzo Ducale).

History went on. In 1886, Count Francesco Donà argues at City Hall that Venice must build a power plant. Local entrepreneurs in the tourism sector answered his call: Carlo Walter and Alberto Treves founded the first power company in Venice, steps from San Marco, which powered lighting at Hotel Britannia, Hotel Bauer, the Café at Giardinetto Reale, and the chandelier at Fenice Theatre. In 1890, the same people partnered with Società Edison to build a steam plant in Corte Morosina, where the Bonvecchiati Hotel now stands, which served the whole San Marco area, the Malibran Theatre, and, since 1893, the Fencie Theatre. Palazzo Ducale was yet untouched by this electrification effort, even though new and different use of the Palazzo did require artificial lighting. Also, in the same years, the precious monument was being heavily restored to safeguard its existence. One of the architects working on the project was Giacomo Boni, who in 18878 published a pamphlet, Venezia imbellettata or Venice in make-up, where he lamented the danger of fire for Palazzo Ducale, which at the time started housing janitors, administrative employees, and the very Fire Department.

In 1896, Palazzo Ducale was to finally get power, though only in some of the inner halls and in the Fire Department offices, the porter’s lodge, the superintendent’s office. The electrification disgruntled many, who voiced their concerns for the supposed ‘profanation’ of a historical palace and the fear of fire. Local press and public opinion were enraged. On July 13, 1896, one Antonio Vendrasco wrote on local paper “L’Adriatico”: “With a feeling that, more than marvel, is more akin to disgust, have we looked over the last few days at a project that is well on its way, and makes no sense or reason, because it corrupts the very nature and the character to the most superb building in the art world: Palazzo Ducale. We are talking about electricity, which is now being installed with haste that would be much better directed elsewhere […] the ardent impulses of these violators of the most beautiful art temple there is must be stopped.”

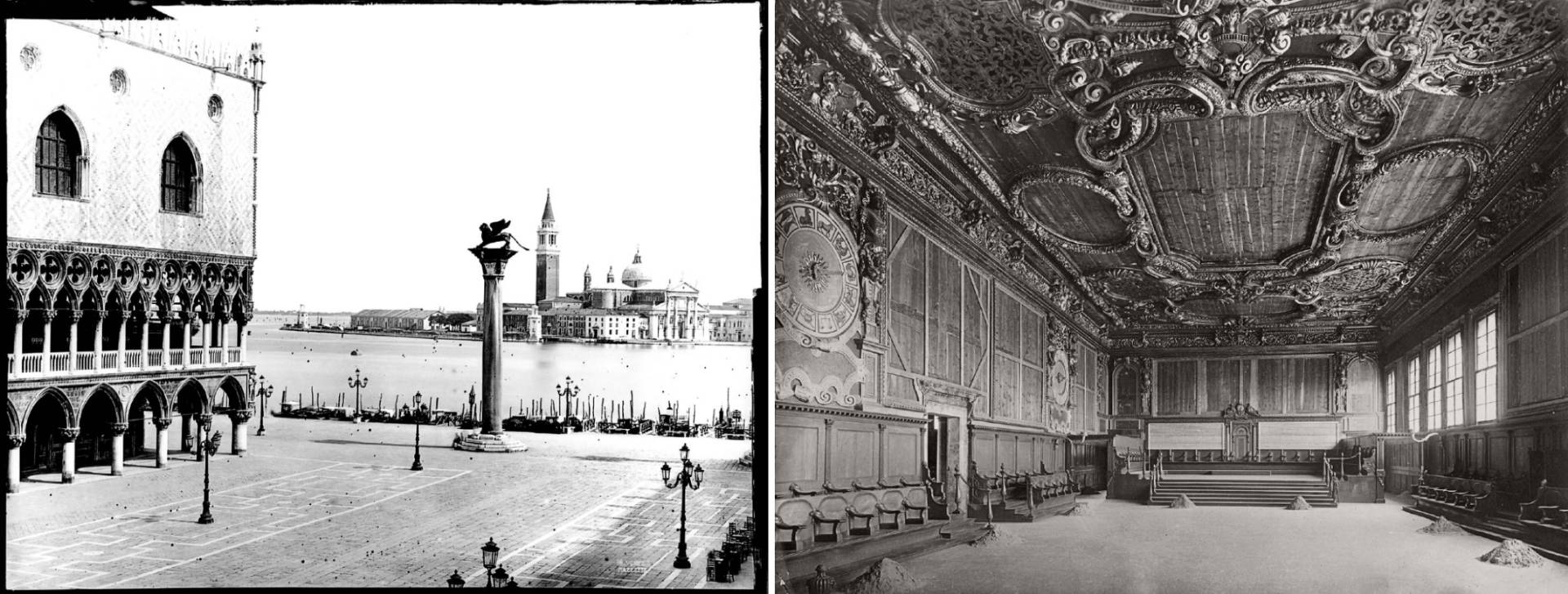

In 1904, the first electric grid powering cast iron streetlamps in Piazza San Marco and inside Palazzo Ducale was inaugurated. (Carlo Naya, Piazzetta San Marco).

Ever since, with the tragic interruptions due to the world wars, the articulation of different visit itineraries, the new functions attributed to the Palazzo, the extension of opening hours into the late afternoon, and the increasing amount of services that had to be offered to visitors required upgrading of the electrical service. Technological innovation helped, as in the recent case of LED lighting being installed everywhere, even, lamentably, in cases that show little respect for the noble monument.

In the meantime, we matured on the front of environmental sustainability, modernization, and more recently, economic contraction due to the energy crisis. The World Day of Energy Saving and Sustainable Lifestyle, due February 16, 2023, has been promoted since 2005. On that day, Palazzo Ducale and many other buildings in Italy and abroad, will dim their lights for several hours.