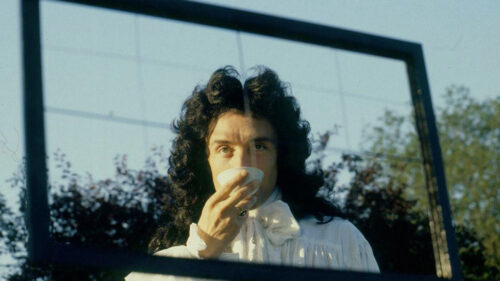

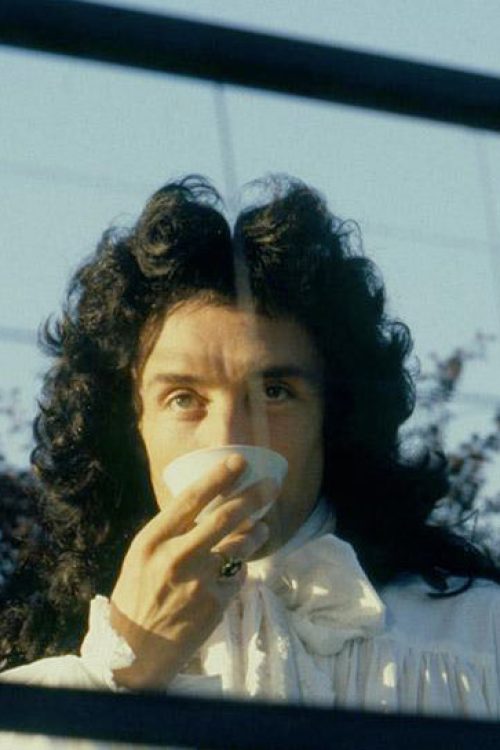

I remember what I felt when I first saw this movie – some forty years ago – as if it was yesterday: a feeling of blinding beauty for the scenery, every frame as perfect and fulfilling as a painting by Poussin, and a sense of alienation, almost of unease. It felt like it wasn’t me watching a movie, but me participating in a ritual of observation whose end goal would be the deconstruction of the moving image, its decomposition into separate parts. It felt as if a sixteenth-century humanist were born again in the 1900s as Greenaway himself to show us an enigma to solve. The solution, though, required a different set of values from the one we are used to. ‘Cinema as an illustrated screenplay’ didn’t quite cut it – camera, actors, plot, script, lights, costumes are needed, to be sure, but they are also constrained in a lower order of factors.

Encyclopedism, coaction and repetition, frenzied attention to framing, scenes that reproduce hypothetical French or Dutch paintings, depth of field as the prime mode to see the world – all of Greenaway’s obsession grew, in this film into the building blocks of a different, new, inimitable, and very, very artificial in its view of history as a continuous thread of enigmas and metaphors. “Don’t let truth get in the way of a good story” (Greenaway). This respect and celebration of the story, in the groove of European painting, is the ultimate sense of Greenaway’s cinema. Sure, not every single film of his is as great as this one, though taken together, they make up a fundamental opus by one of the greatest maestros of modern cinema.

In Greenaway’s formal, catalogue-like, encyclopaedic cinema, landscape is an enigma to solve, but Neville, a painter, cannot, for he limits to “paint what he sees, not what he knows”. Together with Blade Runner, also released in 1982, it can be considered one ...

In Greenaway’s formal, catalogue-like, encyclopaedic cinema, landscape is an enigma to solve, but Neville, a painter, cannot, for he limits to “paint what he sees, not what he knows”. Together with Blade Runner...

No results found.