81. Venice Film Festival

80. Venice Film Festival

79. Venice Film Festival

The Biennale Arte Guide

Foreigners Everywhere

The Biennale Architecture Guide

The Laboratory of the Future

The Biennale Arte Guide

Il latte dei sogni

As a student, curator Chiara Bertola first encountered Bacci’s art with a pure and unconditional gaze; today she still encounters it rereading it with new attention, experience and sensitivity. The result is the exhibition at the Guggenehim Collection, “Edmondo Bacci. The Energy of Light”.

… No one, before me, dedicated much study to his art, and I understood how great my task was going to be as I waked into his studio for the first time.

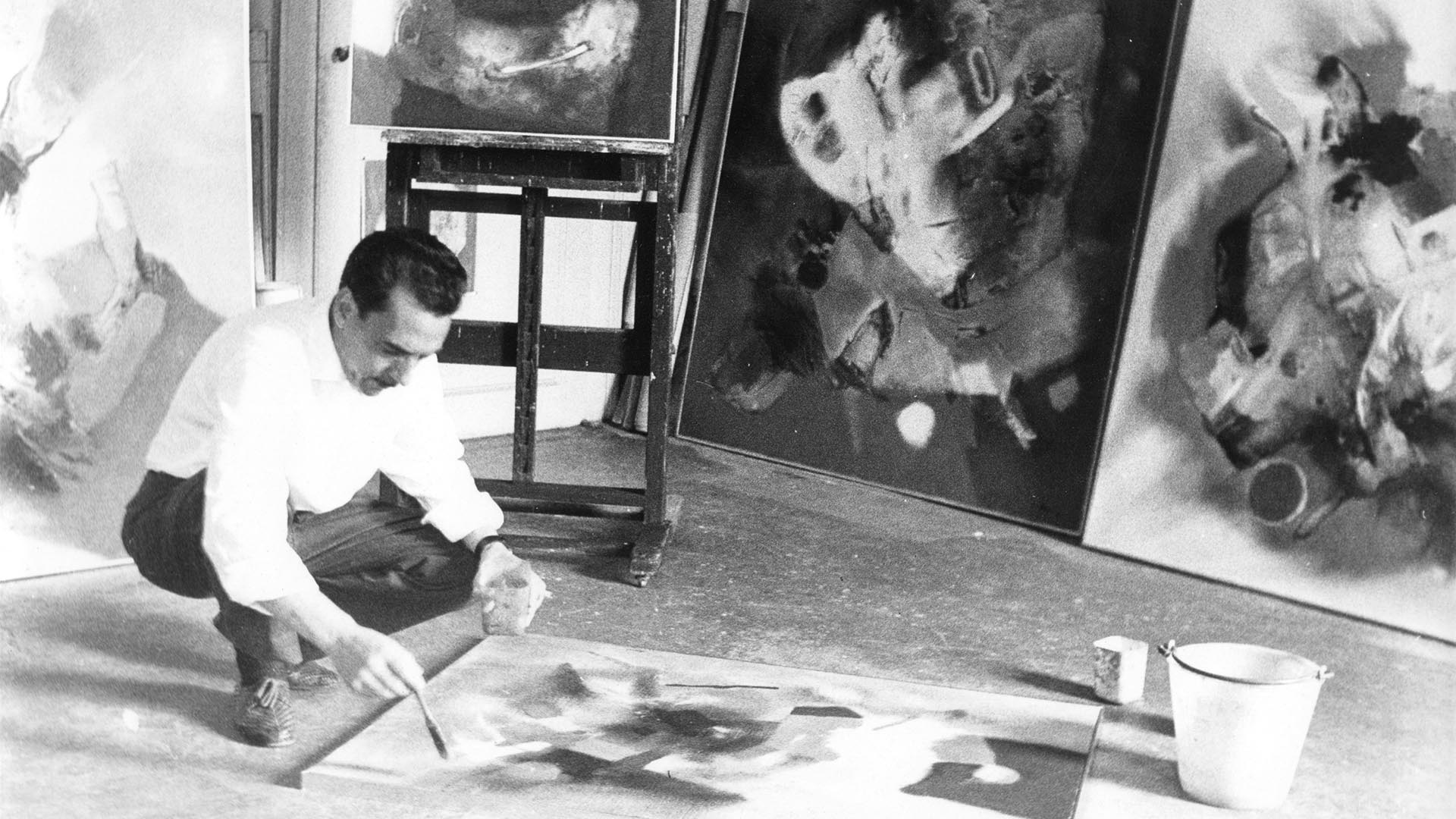

Thanks to a newly-inaugurated exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim Collection and a catalogue published by Marsilio, Edmondo Bacci (Venice, 1913–1978) is given the prominent position he deserves in the Italian and international modern art world. They go even further than that: they convey the pureness of Bacci’s art, because in rediscovering it, it is born again in new light and new creative energy, free from schemes that belong in the past. We owe the rediscovery of Edmondo Bacci to Chiara Bertola, who heads the modern art programme at the local Fondazione Querini Stampalia, and took a job at Peggy Guggenheim’s to revive, critically, the late-1900s season of Venetian painting after monographic exhibitions on Vedova, Santomaso, Tancredi, Fontana. Edmondo Bacci: Energy and Light is, without doubt, the most complete personal exhibition on Bacci, and an in-depth work on the most lyrical season of his artistic life.

Your choice on Edmondo Bacci

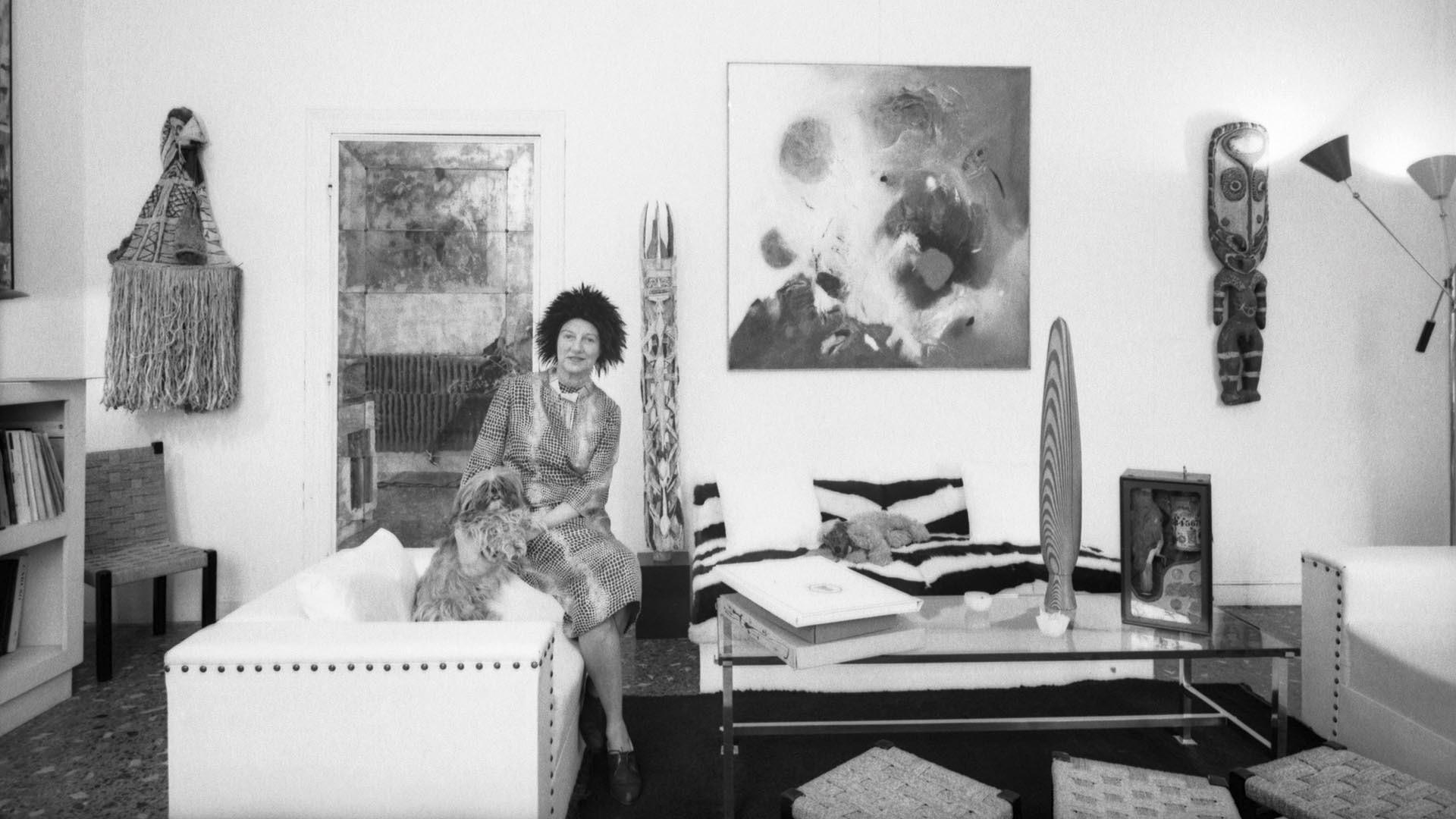

My mentor and professor, Giuseppe Mazzariol, knew I would love working on Edmondo Bacci, which is why he suggested I do so. Bacci is a genius artist, an artist of excellent quality, and has been far too quickly forgotten. As long as Peggy Guggenheim and Carlo Cardazzo were still living, Bacci had someone who could pierce through his shyness and make him open to the world. Without these sponsors, as well as friends, promoters, collectors, and gallerists, he didn’t have the character to assert himself in the world of modern art. Shy, closed up in his silence and his art, he behaved as all of his energy had to be put in the art, and none spared for interpersonal relationships. Some artists are like that. I graduated with a thesis on Edmondo Bacci. No one, before me, dedicated much study to his art, and I understood how great my task was going to be as I waked into his studio for the first time. Guided by his surviving brother Giorgio and wife Denise, who took me in like a daughter, I spent so much time perusing the Bacci archive and make some sense of it. it was the job of an archivist and of a detective. I catalogued pictures, paintings, drawings, mail, notes… and tried to locate the art that Guggenheim and Alfred Barr took to America, trying to make a name for their protégé overseas. He was a relatively prolific artist, though we must remember that his technique was complex, and not quick by any means. All in all, we are looking at some 500 pieces.

A critical essay of Bacci

His art is still very living, and no critics think of it as dusty or outdated. In our catalogue, we made some space for a beautiful, passionate essay by Toni Toniato, the artist, poet, and art critic and historian who was among the few to believe in Bacci and his art, supporting him to the very end. Likewise, we commissioned a critical text to one of the most important American modern art critics, Barry Schwabsky. I was very curious as to what such a specialized critic would say of Bacci’s art, which came to be in a very specific art season – the Informal, Spatialism, Venice, Milan… – at a very specific time, post-WWII Italy. Shwabsky wasn’t really acquainted with the art, he only saw the piece that is at MoMA and a few others, though when he finally flew here, we entertained beautiful conversation and entered Bacci’s dimension fully. He wrote an absolutely beautiful essay that will offer a brand new vision on the art. The other person who I invited to participate in making the catalogue is Riccardo Venturi, an exquisite intellectual and critic, who can draw relationships between different worlds of literature, cinema, modern art. He is also an accomplished author in his own right. Venturi writes of a thread that starts with the Fabbriche (‘factories’), Bacci’s vision on physical labour and political commitment that was strongly felt in those years, giving an ecologist view on the social issue. It is interesting that Bacci’s art 1947 – 1950 may be revisited, today, in a different light than the historical, political, and social context it was born in, and makes it useful to understand a conflict, a social and ecological issue that touches us today.

The artist’s role

Bacci is a very interesting artist because of how sensitive he was. He felt the urgence to adapt his painting into something that could speak the language of modernity. When Fontana and the Spatialists offered him the chance to take part in a debate on theme that he felt very close to, the first thing he did was to react with painting – which is perfectly consistent with what Spatialism maintained and theorized. Bacci’s language evolved, constantly. It strived for experimentation. A young artist, today, will be fascinated by the space building techniques used by Bacci, who employed mixed media. We are talking of the early Seventies, which goes to show the artist’s sensitiveness on the upcoming trend of optical art first, and performance art later. He captured space using painting, first, using coloured thread and few other elements, like Styrofoam and ping-pong balls. The tactile values of painting, spatial ones especially, are to be found in other experiments, too. For example, this circle with iris giving the illusion of motion is an experiment on Cinetic Art, which was avant-garde at the time in northern Italy. Bacci renewed his art at all times, looking for ways to be flexible as an artist. We dedicated an important part of the exhibition to his art of the late 1960s and early 1970s, for they showcase a new, fresh, enthusiastic vision on the spatial coordinates of the time. In short, Edmondo Bacci is an artist that held a strong relationship with modernity, and kept investigating it by adapting and innovating his art. He never withdrew into the status quo, he always came back to the dynamic centre of life. This is, in my opinion, what makes him extremely interesting as an artist.

Style

The exhibition follows the evolution of Bacci’s style for the explicit purpose of highlighting how composite and diverse his work is. In the 1960s, his initial lyricism tensed up, which is why I chose to exhibit very little of that period. I preferred fewer, though very important, pieces that would give the exhibition the rhythm it needs. There’s a point of rupture, too, the 1970s, which show Bacci’s progression and evolution. Exhibited for the first time is a series of drawings, which are very dear to me. I found them packed into a suitcase, back at the time of me working on my thesis. They spent years at the Bacci Archive and now they’re here. They are very important, because they span the whole 1949-to-1972 period – basically the artist’s entire career. What I wanted to do is to offer a new, fresh vision on an artist, a new and fresh perspective, different from the established reading. I think what is apparent, at first, is that Edmondo Bacci is the artist you don’t expect him to be. On a deeper level, he is an artist nobody knows that well.

Edmondo Bacci – the man

At the time, there was no ‘artist’ character. Bacci was an everyday man – mild, polite, passionate though restrained. He came from a working-class family. What is interesting is that his themes are adjacent to those of artists like Vedova, Pizzinato, and others who belonged to the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti. Bacci has been able to take everything he learned and put it into art, which is his voice. When he had been asked why he would join the Spatialists, he answered that he wanted to join in because they focused on what he thought was interesting, too. He just kept it simple, almost consequential. This is what I think, and this is what will happen. There was no big strategy, only urgency: the urgency to express what was within.

Featured image: Edmondo Bacci, Avvenimento #13R (Avvenimento plastico), 1953 – Museum of Modern Art, New York