Micro-Music investigates the new possibilities of listening to digital music, quickly overcoming the limits imposed by categorizations that the contemporary simultaneously imposes and rejects.

The sixty-seventh edition of the Venice Music Biennale promises to be one of the most innovative compared to the canons we were used to. Contemporary music production grew so diverse that it is near impossible to define any categories. Art director Lucia Ronchetti opened a window on modern digital music, offering audiences and critics an open programme that will easily relate with more – shall we say – traditionally analogue composition.

What does Micro-Music mean?

Micro-Music is an investigation in the vast world of digital sound composition that comprises five sections plus one extra, Sound Studies, where the festival protagonists will discuss their work and their motivations before the public. The most representative section of research on European high music is Sound Microscopies.

Listening to music. How will you work with ever-evolving listening technologies?

The Festival will investigate listening sensitivities: listening to electronic music in public spaces, in large night shows, and in private, with technologically-advanced headsets that allow for a complex spatialization of a sound we would normally associate with a live performance in a large concert hall. Micro-Music also shows music that is played in public places, which is a sort of ‘invasion’ and, at any rate, a sensitization of the issue of music listening. We scouted for the composers, researchers, programmers, performers that understand this, and knew how to create new musical realities using the latest technology.

The Festival will investigate listening sensitivities

This kind of music was the prerogative of the avant-garde until not long ago. Today, we may as well call it history. What is the Biennale looking forward to?

In the 1950s, only the crème de la crème could afford working in electronic music labs. Computers were huge and expensive. In the matter of a few decades, sophisticated computers and software are everywhere and accessible to anyone, like this year’s Silver Lion awardee, Miller Puckett. Thanks to the evolution of the personal computer, many musicians all over the world have been able to create truly innovative music. What we at Biennale bet on is finding what have been, over the last few years, the electronic music projects that innovated the most, and started important, recognized trends.

How can we define ‘innovation’ in this music?

Innovation, intended as research for new technologies applied to music, is developed globally by large corporations that make commercial electronic music products as well as by research institutions and researchers in important universities. This work answers the need for a more precise listening experience, more sensitive, more future-oriented, while also gathering innovation stimuli from the active music scene and from the several trends in the field of electronic music compositions—both essential to guide research.

Pop embraced new technologies quickly and freely, though not as much or as quick as high music did.

A gap widened in technological and stylistic evolution in the field of electronic music generated within the different currents of pop, progressive rock, experimental electronics compared to electronic sound research as conducted in large institutional centres founded in the 1950s. I believe what lacked, over the last several decades, is dialogue between these two environments. It could have been prolific dialogue, in fact, and maybe something is growing as we speak.

What were the causes?

A divider too strong between the different stylistic and aesthetic trends on electronic music research, based strongly on the tradition of cultivated European music, which means that, in time, many experimental composers had been underestimated, or outright ignored. The Music Biennale will open with two great American pioneers, recognized all too late by the mainstream: Morton Subotnick and Maryanne Amacher. Subotnick is back in Venice after sixty years—he is ninety now! The reason is to be found in the difference between the complexity of written music and the complexity of unwritten music. For many, written contemporary music is the only one that we may consider research music, but in electronic research and digital sound, which is the theme at Biennale, nobody has been able to create well-defined musical scores. We might say that the programme, the code, is the most evolved and precise form of musical notation as far as synthetic sound and live electronic elaboration go. The code is at the base of all stylistic trends in modern electronic music. Actually, there are strong, obvious historical connections between the two large worlds of electronic music. For example, Autechre are an experimental duo who built on early experimentations by Stockhausen in the 1950s, in turn influencing the first experimental rock bands such as Kraftwerk. Autechre are officially a techno collective, but their techno is sophisticated and complex. Other musicians that are part of the techno world drew from American minimalism as source of inspiration. Among the many, I would like to name two further guests at Biennale who can work on complexity in original, profound ways: Jace Clayton, a theorist, composer, and experimental DJ, and Kali Malone, an organist who can create very static and transparent music based on an idea of deep, meditative listening that changes very slowly, looking for a new kind of sound beauty that is purely digital. Both work with improvisation, not on scores, and can reach levels of complexity that are truly amazing.

Is this a historical pivot point? Like the introduction of polyphon in the 1200s?

Yes, absolutely. We are looking at a Renaissance of musical creation due to the explosion of technological possibilities and the far-reaching accessibility of the same. At the large, famous international festivals, the electronic music composer is always at the mixer. They are performers who control the diffusion of sound in space and react to the presence of an audience. Even in cases where the whole project is prepared and predetermined, we can still talk of conversation with a large public. At festivals such as the CTM in Berlin or Sonic Acts in Amsterdam, it is amazing to see the audience follow the composer/performer with attention and passion.

We are looking at a Renaissance of musical creation due to the explosion of technological possibilities

One might remember of the happenings of American tradition, back in the 1960s…

Micro-Music presents many composers, performers, DJs, creators who work in the form of happenings, like Wolfgang Mitterer and John Zorn, as well as composers who had a more formal education in cultivated music, like Francesca Verunelli and Johanna Bailie, who give out a precise score to performers. The programme is based on compositional sound result, and not on the presence of a given score. Ever since information technology and musical programming existed, there has been not only a score but a programme as well, and the compositional project has been the result of collective work that needs to be recognized. Different, complex codes—all interconnected. I think it is time we recognize the creative team as a whole. In this sense, our awarding the Silver Lion to Miller Puckette, one of the most important coders in the field, is very telling.

What kind of audience will be the most inspired by this edition of the Music Biennale?

What’s important, to me, is that the whole public at the Music Biennale be given the chance to watch concerts of the highest compositional and executional quality. All artists we invited are extraordinary, no matter the style that is proper to each of them. Our public will be free to enjoy each concert and leave, when the performance allows, without feeling bound to any given listening experience. At the same time, I would like to offer the largest amount of occasions to confront the protagonists of the festival, to question them, to understand them better. To this end, we added to the programme conferences and round tables, themselves performative events with musical examples and interactions. The electronic music creator, however we intend this figure, will be at the centre of all meetings.

Our public will be free to enjoy each concert and leave, when the performance allows, without feeling bound to any given listening experience

Sound installations

Another way to listen to electronic music is the one offered by Sound Exhibition/Sound Installation, where several sound installations have been created and positioned in neutral spaces that in turn allow the audience to physically enter the sound, visit it, and explore it, all without the timebound experience of a concert. I’m thinking, in particular, of two installations by Louis Braddock Clarke and Alberto Anhaus, at the Sale d’Armi. Louis Braddock Clarke is an English sound artist and amateur geologist who works with metal slate resonance. Alberto Anhaus is a composer, drummer, and sound artist who will take us into the underwater world of the Venetian Lagoon to see algal decomposition and the sound of their habitat. In his installation, the habitat will be visually and olfactorily perceivable, though unknowable in its sound dimension.

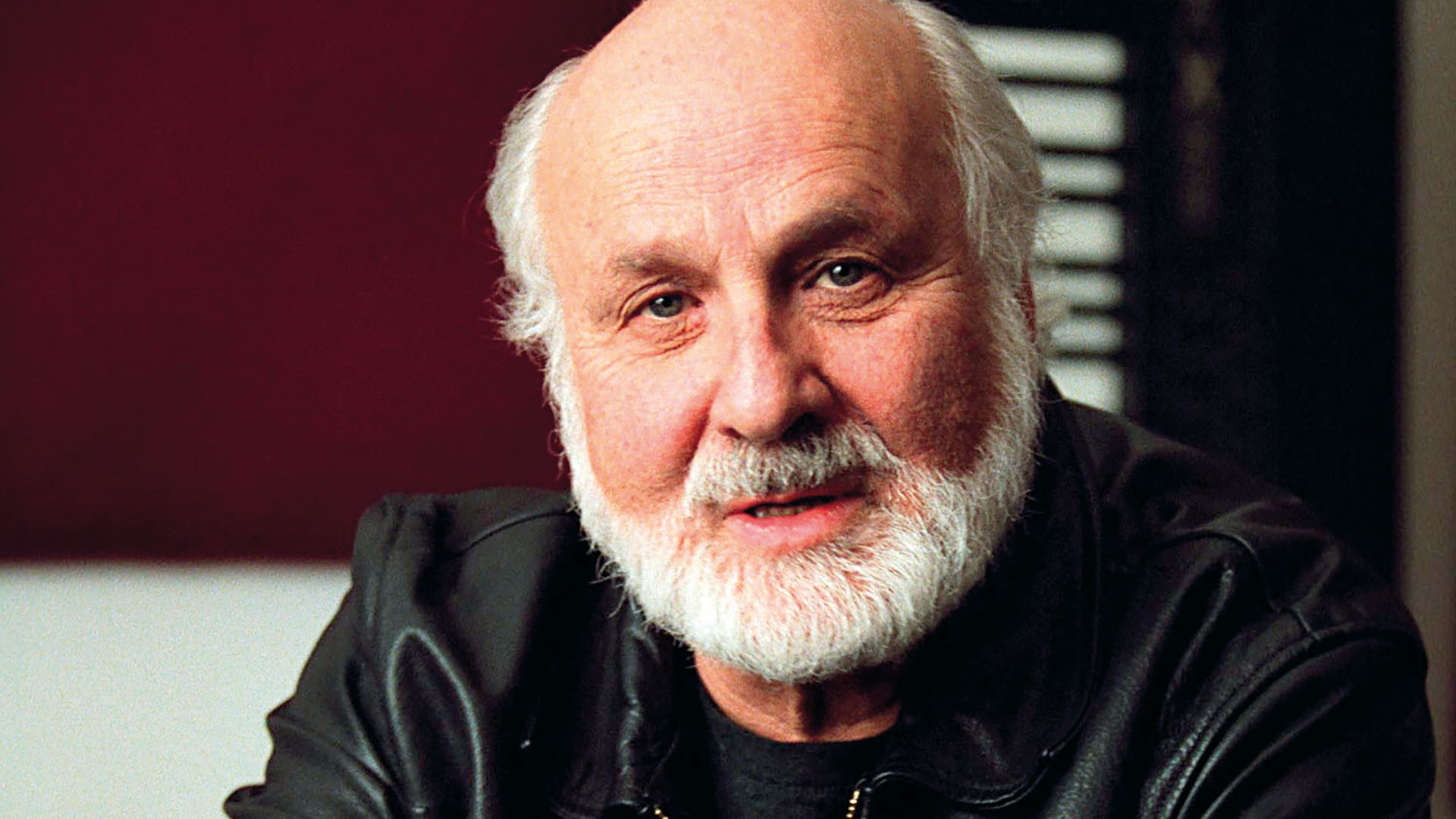

Featured image: Lucia Ronchetti, Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia – Photo Andrea Avezzù