Son of French cinema icon Alain Delon and actress Nathalie Delon, Anthony tells his story unfiltered in his book Entre chien et loup, a heartfelt story of a life that is extra-ordinary in all possible meanings.

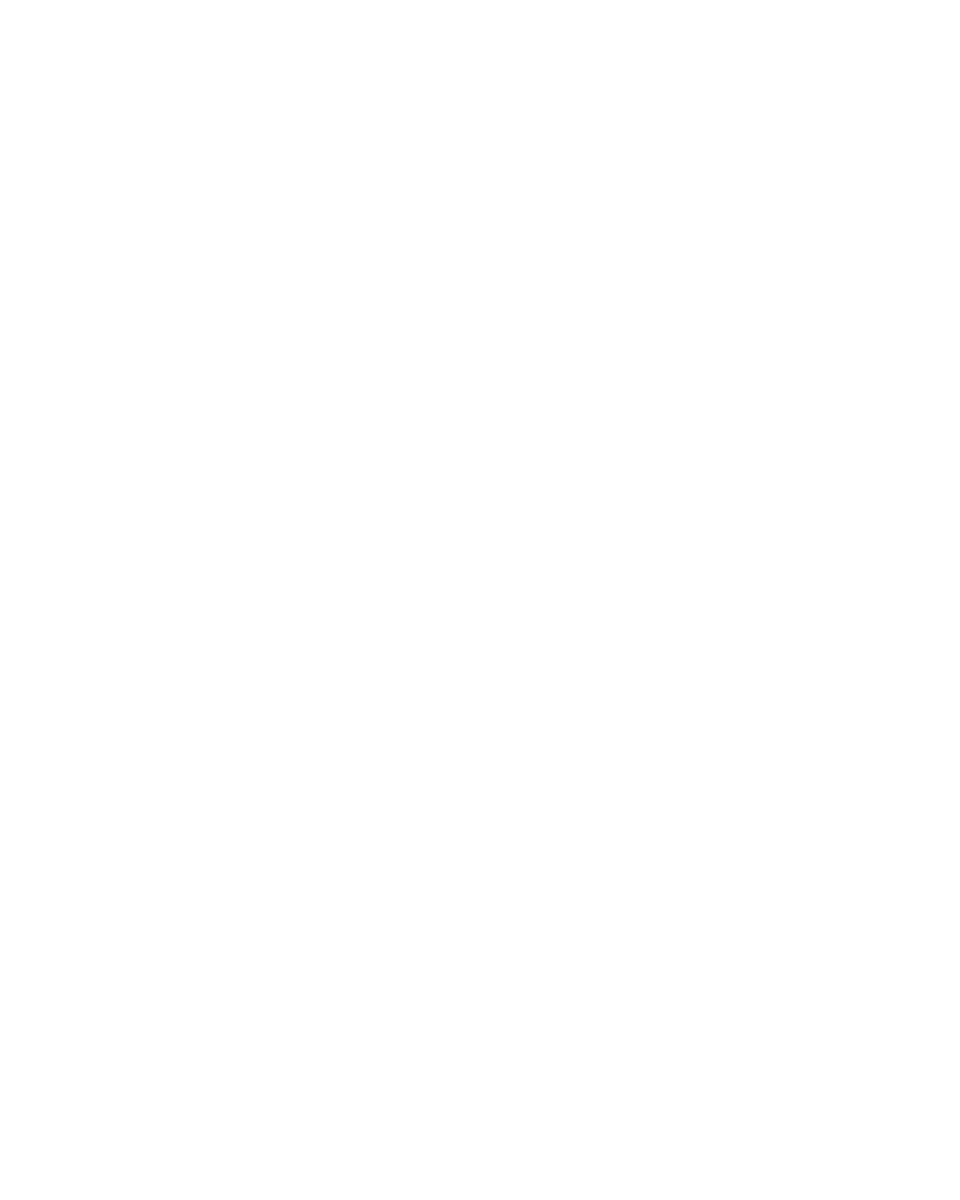

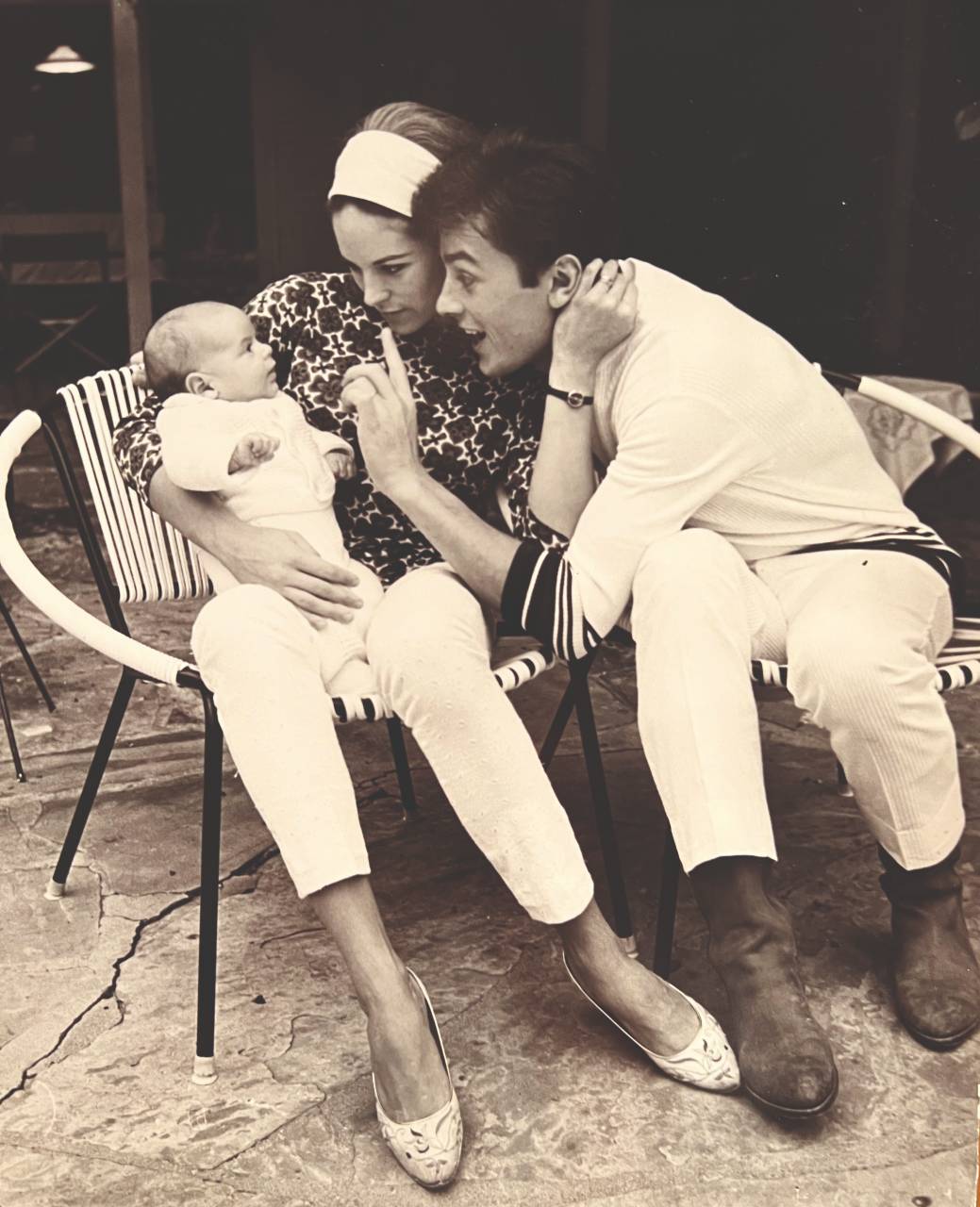

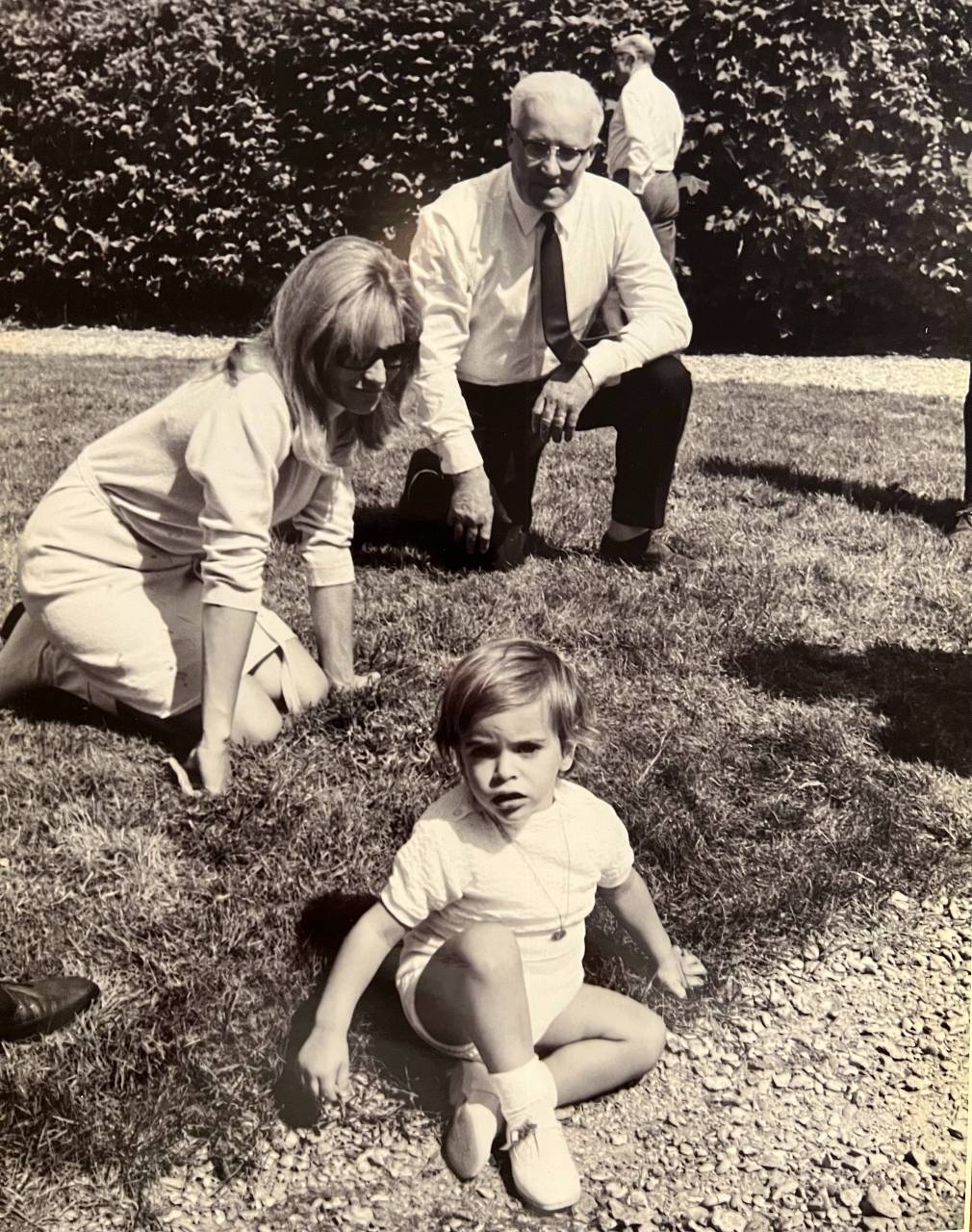

Biopics are all the rage now, but whatever fashion dictates and whichever stories end up being the most interesting, what really hits home is the sincerity that writers, themselves the protagonists of the story, adopt when they tell us about their lives. A prominent example is the extraordi – nary, engaging autobiography authored by Anthony Delon: Entre chien et loup. The son of French cinema icon Alain Delon and actress Nathalie Delon, since age four, Anthony spent time alternately with his father and new partner Mireille Darc and with his mother, godfather Georges Beaume (also the talent scout that launched Alain’s career), and Lolou, his French-Sicilian-German nanny.

Now aged fifty-eight, Anthony Delon lays it all bare: no secret is spared in this very personal existential journey, which offers readers the heartfelt story of a life that is extra-ordinary in all possible meanings – rebellious, crazy when needed, not devoid of suffering, abandonment, and loss. Nostalgia veils the figures of the protagonists, many of whom are long gone, though life always finds a way to push forward, and Anthony’s words balance carefully curiosity, compassion, disappointment, acceptance, anger, forgiveness. A narrative mosaic that inspires and moves. A real page-turner, too. We wanted to know more, and we reached out to the author. This is our interview with Anthony Delon.

Why did you write this book?

I began writing because I was going through a rough patch in my life. I was vacationing in Italy with my family. It was August, and my mother was very ill – she had only a few months to live. A year before, my father had a stroke. My godfather passed earlier on, too, and so did my nanny. Mireille Darc, a very important person in my life – dead. All of a sudden, I was scared. I realized that all the people I loved were leaving me. I felt the need to pay homage to these people, who were my guides. I wanted to carve our stories into marble. What prompted me to write was seeing my mother dying, my father struggling, I just didn’t know what would happen the next day… I felt the urgency to work on my memories. It was a way, for me, to give back some life to those who were gone and to those who I wanted to cling to.

Before we get into the story… what strikes about your book is how nicely your writing flows, a river that pours out freely from the pages. What does writing give you? Is it therapeutic?

I believe writing is, in some measure, therapeutic, yes. I found out myself as I was writing. The mere fact of facing a blank page forced me to put down my stories clearly, in black and white, and at the same time, it helped me to detach from them a bit, and I found that to be quite healthy. Going about that was necessary to best analyse what has happened throughout a lifetime.

Between dog and wolf.

It is a French idiom that my godfather once taught me. We were out in the countryside, looking far into the horizon, and he whispered to me: “Look, it’s so beautiful. We don’t know if this is night or day, all we know is that it’s magic.” It goes beyond that: the dominating power of the wolf, the passage between childhood and adolescence, the moment a man grows powerful. It is a transitive title. It may also mean the passage from love to hate – there is a very thin layer between those two feelings. It is easy to step from one to the other, just like from day to night.

You use the story of your father, Alain, and your mother, Nathalie, and later that of Mireille Darc, to tell us about yourself. Two themes seem to recur: innocence, and loss of innocence. How much have those elements been crucial in generating your identity of child, first, and man, later?

Innocence is not something you lose quickly, and you only lose it once you realize it. A child is subject to events, to his parents, to everything that takes place around him, and he cannot make much sense of it all. At some point, little by little, he begins to question what happens, and to understand what happens. He is not a passive, naïve subject anymore. With time, he grows cognizant of his life and draws his own conclusions. That’s the moment when he grows up and lose innocence. Certainly, it is all far from simple, but in short, that’s what goes on in a child’s life. In my book, I wrote about the child that we all have within. As an artist, I believe it is very important to voice the innocence of this child. Though this is artistic creation, it is not life. The loss of innocence can, in some way, define you as a person in all its contradictory complexity. The main theme of the book, however, is abandonment and the cycle of suffering, forgiveness, resilience, reconstruction, awareness, love. Love is everywhere in my story. Can two people who love each other hurt each other? Those who love with a passion – yes, they can hurt one another. When two people are complementary, and love with passion, that’s when love can turn into a deeper feeling, more selfless and generous. At that point, you cannot hurt or get hurt. But when two people love with passion, and they’re not complementary, they’re too similar maybe, that’s when love can hurt. Passion amplifies fear, weakness, trauma. If you suffered from abandonment, then you fear being abandoned. The fear and pain of childhood resurface. They say passion lasts two years. Personally, I believe it can last longer, but in this case, two people will destroy each other. They will love and destroy each other, all at once.

Absence and loneliness as education. In life, you learn some things just by being alone. Was it any different for you?

I felt abandonment both in the case of my father and in the case of my mother. With my mother, it was maybe even stronger. As a child, you need your mother more than anything else. As far as loneliness goes, well, we are alone when we’re born and when we die. We are always alone. We are alone when facing joy and pain. We may be accompanied, we may have people supporting us, friends and partners may dull the feeling, but I have always thought I was standing alone before myself. It’s everywhere in my book. I have felt alone so often, more so than what usually happens. I think this influence my becoming who I am today. This existential condition allowed me to write, to create, because it forced me to live in a world of my own. I can stay on my own for a long time. Loneliness does not scare me. I spent days walking in forests alone. I must also add that up to a point, we are also born that way. It’s not all about life circumstances. For example, my mother was not a solitary person, whereas both my father and I are. my mother feared loneliness: in her last few weeks of life, she would tell me: “I don’t want you to stay too much on your own, you look so much like your father…” I told her not too worry because, loner as I am, I love strongly, and I believe this will be my salvation. You have kids yourself.

How did you grow from son to father?

Becoming a father made me grow. In fact, it completed who I am as a person. The responsibility is so strong and so overwhelming it changed me. It made me more tolerant. At the same time, I had to understand very well what I was teaching my kids. It is a long, difficult journey, and I worked on myself a lot. I didn’t want to repeat past mistakes. I saw clearly what I was lacking as a kid, and it healed me. What are the most vivid memories of your adolescence that may summarize your relationship with your mother? My mother and I talked a lot. She would talk with everyone. She was a generous person with a strong character. We clashed, too, but quickly forgave each other. Sometimes, days passed before we would speak again, but love always prevailed in the end. Generosity, clash, exchange, love – that’s how I would sum it up. When she fell ill, there was little conflict, too. Facing death changed her. She had been abandoned by her father, too, and her mother died very young. She had trauma, that’s why she sought, no, she initiated conflict. However, the last few years of our relationship have been quite serene.

Important feminine figures influenced the story of your life since childhood. How do you remember said influence?

My mother, when she was around, influenced me greatly. Lolou and Mireille, too. Within me, there’s a feminine side that is very developed. A sensitivity. I have been raised by women and I can communicate with them more effectively. Women are more intuitive, more charming, and I don’t mean physical seductiveness, but their inner essence of their femininity. Women have absolutely had an important role in my life. I have two daughters who have been living with me for the last seven years. I took care of them on my own since their mother left for America. They were quite young, but I managed, and they made me a better man in return. They made me understand things I never quite understood before. Everything happens for a reason. Truly, women are the heroes of our days.

How did your book’s success change you?

It benefitted me. It was such a pleasure to write it on my own, I am so proud of it. Though what gave me the most, the part of success that most fascinates and strengthens me, are people. The themes of my book are universal: abandonment, family, childhood, adolescence, the hurt that keeps our inner child from living, the look for balance in our lives. This is my story. Many people, in many different settings, told me how the book gave them the key to understand some of the more obscure sides of their lives. They made them feel better. This feels better than commercial success ever might, for it makes me realize that I did something good, something useful for me certainly, but in some sense for other, as well, for my readers. When you seize the moment, the feeling, so fully, that’s when the book becomes stronger than you are, because it speaks to people and help them open their eyes. It gives answers to many unresolved questions of existence in this complicated world. This is really wonderful, a feeling so strong that I’ll never forget.

Your relationship with the past and the passing of time.

I am a very nostalgic person, which is not to say it is a depressive demeanour. I feel time passing, I feel like carrying a bit of it with me… it is a bit sad, a bit nostalgic. I feel nostalgic for a time that is not there anymore, and for amazing people that I met and who are not there anymore, either. As for the time that is left, well, I hate wasting it. The more I walk on, the more I hate wasting it. If I go see a movie and grow bored after half an hour, I just leave. At theatre, no, out of respect for the performers. I mean, it’s not impatience, I just don’t want to get bored. Time goes by so fast that I don’t want to lose any of it. That’s it.

Your book is, indeed, a screenplay, which will soon become a TV series. What will your creativity add to the upcoming adaptation?

At first, I didn’t want to write a book, but make a movie or a series. I wanted images, not words. In fact, film adaptation rights had been bought before I published the boo, which I was asked to write, anyway. I refused at first, but later I realized how interesting it would be to write a book before making a film out of it. It would have been useful to feed scriptwriting and help develop the project. Now the book is there, and I will be a consultant in the production of the series. I will give my best to give ideas, but I won’t work directly on the writing or on casting, that I won’t do. The series is a production of Media One, with Dominique Besnehard, who also produced Call My Agent! It will be filmed in English.