There are only a few places in Venice where you may see the cuoridoro (lit. ‘goldhearts’, due to the similarity of the Italian words for hearts-cuori and leather-cuoi) a set of manufacts that originated in thirteenth-century southern Spain to later spread out to Constantinople and Venice. In the sixteenth century, Venice counted over seventy shops that made them as well as active and lucrative trade of the same.

Decorated leather was widely used to upholster backrests, screens, curtains, fanlights, drapes, rugs, cushions, chairs, chests, sheaths… due to its toughness and insulation properties. All the most important churches employed leather as wall upholstery to alternate with columns and cover the altars for solemn mass. We know as much by consulting contemporary archives and inventories. Leather, though, is not eternal, and it perishes over such a long period. At the Redentore Church, there are still a few antependiums likely made by Francesco Guardi, which are put on show yearly on occasion of the rites to commemorate the delivery of the plague from Venice. Some cuoridoro have long been lost, replaced today by regular upholstery in the four columns of the main altar and the eight columns that support the central dome of the basilica as well as by the precious golden velour made by Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua, showing beautiful drawings of architecture, plants, and flowers.

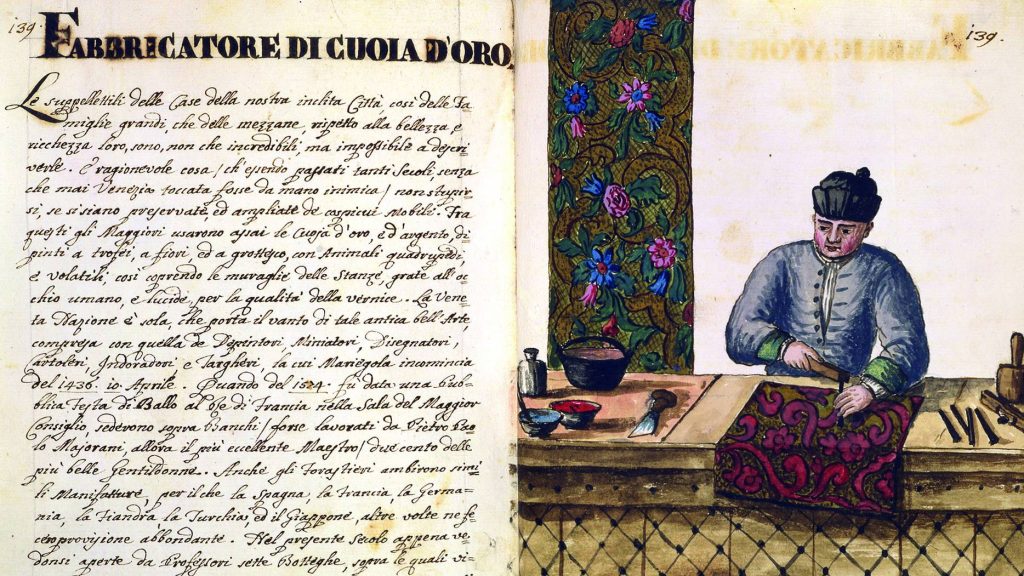

The most beautiful decorations of Venetian palaces also used leather to give character to their halls as well as to insulate them in the winter. The practice can be appreciated, today, in the halls at the rooms that housed the Quarantia criminal and the Conservatori e gli Esecutori alle leggi, both at Palazzo Ducale. Those rooms are filled with cuoridoro. Other rooms, in addition, preserve the hooks that were used to hang the same, back in the days. In the Armeria, we will find many parade shields of exquisite quality and ancient quivers, also decorated with cuoridoro. Further examples, all publicly accessible, are in a room at the Casino and at Palazzo Papadopoli on the Grand Canal. Jan van Grevenbroeck’s Gli abiti de’ veneziani, (‘The Venetian clothes) includes a drawing of a cuoridoro maker and the following text:

“Furnishings in Venetian houses, both in noble families and middle class, are both incredible and indescribable. Reason suggests that since Venice has not been attacked by enemies in centuries, it is no wonder so many are so well preserved, including much décor. Ancestors used copiously leather plated with gold or silver, flower paintings, nature scenes… thus opening the walls into the several rooms in a way that pleases the eye, so shiny in their excellent varnishing. The Venetian Nation is the only that can boast so much beautiful ancient art. When, in 1574, a ball was thrown in honour of the King of France at the Doge’s Palace, two hundred noblewomen sat on furniture made by Pietro Paolo Majorani, then the best craftsman there was. The foreigners loved such beautiful furniture, with Spain, France, Germany, Flanders, Turkey, and Japan buying much.”

Very apparent in the cuoridoro is the influence of Islamic art: flower (especially tulips), fruit (pomegranate), woven together into bouquets, wreaths, festoons… as well as animals, puttos, heraldry, and religious imagery. Geometric and grotesque imagery wa salso common.

Over the course of the 1700s, the use of wallpaper became so popular that leather art declined dramatically. Grevenbroeck mentions how in the 1760s a mere fifty craftsmen remained. After 1806, with the suppression of guilds, the craft of cuoridoro was all but extinct. By the late 1800s, one craftsman alone kept the art alive. At the same time, historians and collectors grew interested in these objects and in the few remains that were to be found in ancient palaces. Part of these ended up in the collection at the Correr Museum into a diverse repertoire of a Venetian art long disappeared.