Venice pays homage to the great Spanish maestro, a rightful heir of Buñuel and a cruel iconoclast who passed away earlier this year. Carlos Saura became part of the Spanish avant-garde aged merely twenty, possibly due to the influence of his painter brother Antonio. The same influence will be apparent in Carlos’ cinematography. The filmmaker is a bridge figure that touched over forty years of cinema, including surrealism and Italian neo-realism. He is also a master and inspirator of the third name of the Spanish cinema trinity.

Is it disrespectful to call it a trinity? Luis Buñuel, Carlos Saura, Pedro Almodóvar – together, a century of idealism and contraposition. It might be disrespectful, but so was their art and the intrinsic message therein. Sometimes hidden, intuited, dissimulated, the message was rebellious in nature, and the messengers blatantly free. They were fierce opposers of any form of intolerance and repression: sexual, intellectual, political.

A pupil and a teacher, Carlos Saura made a lasting impression on Spanish, and international, cultural history, tying his name to a kind of art that blends reality and imagination, consistent narrations and grotesque transfigurations. Building upon Buñuel’s teachings, he systematically worked on both social and intimately personal issues, never resorting to simple chronicle-making (that wasn’t his style at all) and immersed them in satire and allegory – not that he had a choice, under Franco.

Three decisive meetings changed his life forever. The first was with Rafael Azcona, Marco Ferreri’s alter ego and the screenwriter for some of his most peculiar works, like Ana and the Wolves and ¡Ay, Carmela! The second was with Geraldine Chaplin, who turned into his muse and a real icon of cinematography as well as his partner in life. The third was with Antonio Gades, the father of flamenco, with whom he made film explicitly inspired by dance: Blood Wedding, Carmen, El amor brujo, Flamenco, and Tango. These figures had been instrumental in his education.

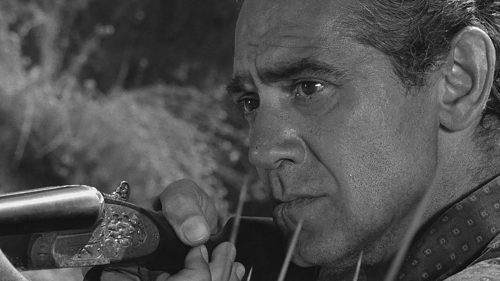

Shot as Franco’s regime was enjoying full establishment, The Hunt (1966) shows the delirious, twisted psychology of three Spanish Civil War veterans during a rabbit hunting party, under the naïve eye of the child of one of the hunters. In a desert-like scenery – ...

A hunting party turns into a massacre in what is a clear homage to Saura’s maestro, Luis Buñuel.

The wounds of Francoism reverberate in a tragic family drama feeding on nightmares and not-quite-revealed realities.

A crossroads of jealousy turned by Saura into a plastic combination between García Lorca’s poetry and Antonio Gades’ ballet.

Manuel de Falla’s ballet transposed onto the suffering of real life, so real that it takes us behind the scenes at rehearsal.

The tragic epilogue of vengeance following a brutal rape. There is no final catharsis, here.