As per tradition, just a few days before the Start! of Venice 79, we met with the Artistic Director, Alberto Barbera, to let him tell us about a Festival that is 90 years old this year, but wears them well.

The 79th edition of the Venice Film Festival promises to be among the most anticipated of the last twenty years in terms of contents, protagonists, structural innovations. Twenty years strongly marked by the curatorial visions of Alberto Barbera.

The fourteenth Festival for Alberto Barbera. Continuity and changes…

Since the first edition I curated, in 1999, everything changed. These changes, though, have never been abrupt – it has been a continuous transformation, sometimes undetectable, whose dynamics developed slowly over time. A latent, constant revolution. When cinema evolved from silent film to sound, now that was epochal, abrupt change. People at the time felt a revolution unfolding before their eyes. Today, we see things slowly creeping forward, sometimes walking backwards, changing route constantly. We all know what changed, of course: new distribution platforms, the hardships in traditional production and distribution networks, all that change in the culture, the industry, the institutions that work with cinema. If we look at the Venice Film Festival, though, its prime meaning hasn’t changed one bit: to make your film known, to test its impact on a sophisticated audience, as naturally is the audience of an international film festival. Our audience is very diverse, too, with hundreds of experts and industry professionals as well as thousands of film aficionados and regular audience who reconstruct what, in the end, will be the larger audience of a film. What also changed at the VFF is our job as a selection committee. We work much harder than we used to. The pandemic influenced the regularity of film releases – in fact, they had been halted for months. Many accumulated and eventually, there was a bunch of movies that hadn’t been distributed yet and were pressing for their theatrical release. I may say I never stopped watching movies over the course of the last year: I am talking about four or five in a day since December. Our job doesn’t end with watching, though. It extends beyond that in maintaining relationships and networks we are accountable for. And then there’s the organization of the Festival. This year, I observed how much stronger is our relationship with producers. On their part, I felt some form of apprehension and worry that felt new to me. Never as much as this year have I been pressured to include some movie or other in the final line-up. There have never been so many movies made in such a short time. It is all about the uncertainty of a situation that depends, in large measure, on production workforce and distribution, who see their vital space threatened by the dramatic changes that affect their world.

The Festival at the centre

Being in the line-up of the festival means getting the larger public to know your film as well as having a quality label attached to it.

It means to be above others, to distinguish oneself. Conversely, the responsibilities of the festival grow just as much, what with the expectations that we must meet, both from the point of view of filmmakers and audience. Today, like never before, we realize how much our ‘yes’ and ‘no’ mean for a movie. Not only in a commercial sense. Even the most experienced professionals are just as stressed as debutants.

The topics: intimacy, existentialism, families, integration, politics, history, and biopics

We are researchers, we are curious, and we take risks – after all, our job is to pick 23 films out of 2,300. As I was saying, so much cinema has been made lately, both in Italy and abroad. Some- times, quality suffered because of it. We should also mention that it was not only the platforms asking for more and more content, but also public policies that sponsored productions. Let’s be clear, here, sometimes films were produced that didn’t really have to be. This pressure upon filmmaking then collided with rising produc- tion costs due to the pandemic. Some of the films we picked didn’t suffer from this, and we picked them for that reason. These films took three to five years to make, and we may call them well-rounded and finished, like Iñárritu’s or Baumbach’s latest. Some of the films submitted were rushed, hasted. Those who produced a movie just because, in fear of being pushed out of the market, inevitably made films of dubious quality. This will have medium-term effects, because it will alienate audiences and damage trust and credibility. It will be hard to gain those back. Think of Italian cinema and how hard it was to rise in quality again after the dismal average quality it had in the 1990s. Now, back to this upcoming 79th Venice Film Festival. There are many autobiographical films, or self-inspired, shall we say. There are also many films on parental relationships, as if two years of restrictions inspired authors to focus on this theme. These films understand the suffering while showing grown-ups’ inability to do the same. History also has a growing place, as do the stories of different countries at a moment of global instability. We will see and hear different readings, different themes, different identities.

The Academy’s participation at the Venice Film Festival

We have been trying to work so closely with such an institution as the Academy for a long time. Over the last ten years, a connection has been growing between the two, with many films beginning their journey at Venice to later being awarded an Oscar. Last year, a board member followed the several titles screened here at Venice and met me to tell me how much they appreciated the Festival – the line-up, the panels… we then decided to make this relationship official. The Academy soon showed interest in understanding how the VFF works internally, and will be presenting their new course of action here at the Festival. Not much about the individual enterprises, but their guidelines for the future. For us, this is obviously an important acknowledgement and the legitimization of a role and a prestige that we earned through the hard work of all involved. Although we work very closely with producers and distributors, we never took the easy way out as a selection committee. I think it all paid out in terms of reputation in the end. We are very clear in our approach and work hard to maintain the Venice Film Festival’s reputation, which is the only way that allows us to keep our head high and not bow to pressure.

A wide and open look on the world, and a conspicuous absence

The absence of China, safe for a couple entries, is certainly conspicuous. The main reason, aside from the pandemic, is censorship. It may be sly, underhanded, what have you, but it is strong. Unwanted filmmakers are prevented from obtaining the necessary funds to produce and distribute their work. The Chinese government puts an inordinate amount of pressure to stop certain directors from working and to prevent what films the do make from being distributed, least of all abroad. However, diverse points of view and new geographies do have space in the Venice Film Festival, and they surprised us for their ability to make amazing productions in places we struggle to even think about being envi- ronments conducive to filmmaking. It is with great pleasure that we see governments supporting filmmaking in countries that never employed such policies. Cinema promotes the culture of their territories and is an incredibly powerful cultural vehicle. Young talents are everywhere, even in places that don’t even have cinema theatres. From places that never stepped foot on the red carpet we received works that are amazing for the ability of their directors in mastering the language of images. Also, I’d like to mention Iran, who has a long cinema history and that keeps surprising us with excellent work. In short, there will be much surprise all around.

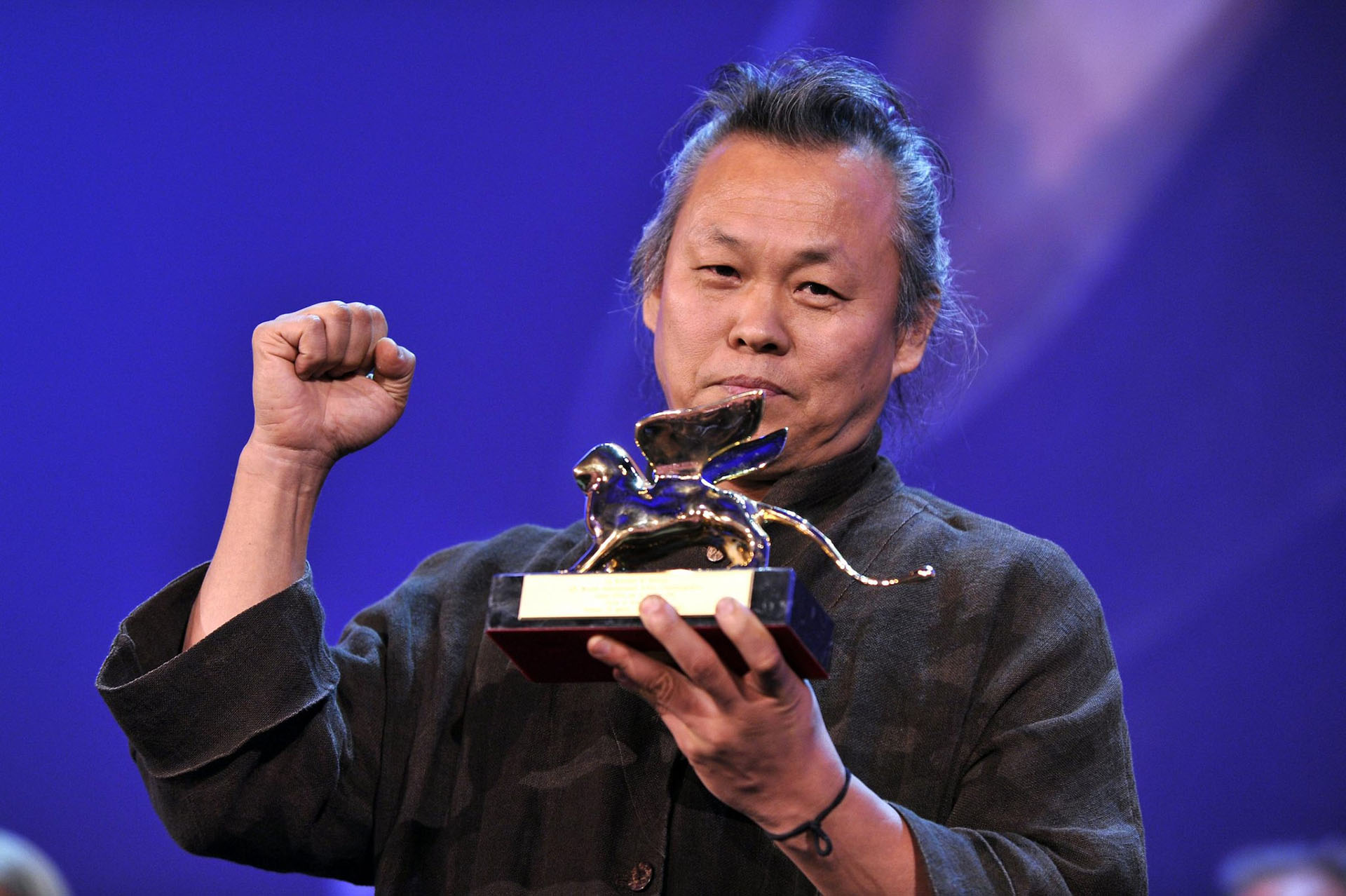

Jafar Panahi – incarcerated by the Iranian regime – and Kim Ki-duk – who unexpectedly died while completing his latest film.

The Estonian producer of Kim’s film has been talking to us about it for two years, then the director died in December 2020 due to COVID. Principal photography had been wrapped and the movie was being edited. Kim Ki-duk, by the way, left precise indications on how he wanted the film to be edited. Financial difficulties delayed work, though fortunately, the film has now been completed and we will be able to show it at the Venice Film Festival. We all thought it was natural to show Kim’s latest film here, since it was Venice that made Kim known to the larger public with The Isle in 2000 and awarded him the Silver Lion for 3-Iron in 2004 and the Golden Lion for Pieta in 2012.

About Jafar Panahi – those who saw his film say it is his best in the last several years, the most accomplished and aesthetically impressive. This is Panahi’s fourth film produced while underground. By the way, this shows clearly the hypocrisy of the Iranian regime, who prevent Panahi to travel outside of Iran while knowing that he is actively making films. These films, in turn, do get out of Iran, and are internationally recognized. Everybody knows, nobody speaks. Only dictatorship can explain that.

Due to Panahi’s arrest in July, the situation precipitated. In contrast with earlier arrests and trials that ended with him being sentenced to house arrest, then to a travel ban and to a ban on filmmaking, we have been informed by people who are close to him that Panahi didn’t take a plea deal, and chose to go to trial. This choice means he is willing to openly challenge the regime and will very prob- ably result in harsh punishment. The regime has always been aggressive towards him and things don’t look like they’re improving. The situation, on a global level, is very worrying. I’m thinking of Turkey, where filmmakers can hardly work if they’re somehow at odds with the regime. See the recent case of Çig ̆ dem Mater, who has been given an eighteen-year sentence for only thinking of founding sponsorships for the making of a documentary on the 2013 Gezi Park protests. Western countries, too, often fail miserably in trying to support the value of democracy – censorship is often hidden under the veil of hypocrisy. Italy is no exception.

Italian cinema: looking in, looking out

The cases of Pallaoro and Guadagnino show quite well how one can work in an international environment and never let go of their authenticity and identity, never reneging their roots nor their home country. All the while, thanks to their open-mindedness and distance from environmental constraints, they make movies that don’t necessarily have to conform to Italian aesthetics. If we didn’t know who made Guadagnino’s Bones and All, we might as well ascribe it to an American director. Bones and All is about a piece of American history that is less known this side of the ocean. We naturally feel disoriented when we see the backwardness, even the sheer misery of the very heart of this country, the Midwest, which has so little in common with the coasts. The same, in a way, may be said of Andrea Pallaoro, who left Italy as a young man to move to America and work with American crews, the only exception being his Hannah of 2017, which passed at Venice in 2017 and earned Charlotte Rampling the Volpi Award. Much like Guadagnino, Pallaoro sees making a film abroad with an international cast a normal, logical condition. This naturality and authenticity allow him to never lose his nature, whatever the project he works on may be.

On the other front, the more closely Italian one, we were able to pick excellent films, no matter the overproduction which we discussed earlier. Amelio’s Il signore delle formiche is his best movie in the last twenty years. There are several other strong, emotional films, too. I’d like to mention Susanna Nicchiarelli, whose Chiara adds another piece to her strong, personal artistic itinerary in terms of language, aesthetics, content, as she rediscovers feminine figures who, for different reasons, ended up being cancelled from history.

Orizzonti and Orizzonti Extra

It’s great to see how much these sections grew in such a short time. My intention was never for them to be a self-referencing, niche programme of movies – nothing of the sort. To be sure, Orizzonti is a space that is less constrained by the canons of a great film festival: it is more open and free, and that’s the reason why it is also the most inclusive section and why it can grow in any direction. Orizzonti is by no means a second-rank programme. Last year, I offered French director Jean-Paul Salomé to place his La Syndacaliste, starring Isabelle Huppert, in Orizzonti. We are talking of France’s greatest actress and one of the world’s greatest… In Orizzonti, we like to shake things up a bit. There will be films by established directors like Pippo Mezzapesa (Ti mangio il cuore) and debut films, which will of course benefit by proximity. The opening movie, this year, will be Princess by Roberto De Paolis, who has a very personal approach to filmmaking – half fairy tale, half documentary. He spent two years with Nigerian sex workers to gain their trust. Among them, he found his protagonist, a natural-born actress. The movie would have been at home even in the main competition, but Orizzonti fits quite right, as well.

Venice Immersive – what’s new?

The section grew even bigger – physically, too. It will take up every building in the Lazzaretto Vecchio island, with one section devoted to the VR market, which is a new addition. It all takes place on the island, over 2500 square metres housing impressive interactive installations. Since the Venice Film Festival is the only great film festival with a section expressly dedicated to this pro- duction technique, it is a reference for everyone who is interested in it: filmmakers, technology enthusiasts… and it shows the VFF’s ability to grow in all directions.

The Golden Lion to Paul Schrader

An all-around great author, whose stories made the history of cinema. Schrader made movies that changed the world, just think of what American Giogolo meant when it came out. He works on controversial films that never look for appeasement. As a director, part of his story is here in Venice, and we felt we had a duty to celebrate it.

Catherine Deneuve

There’s one icon that has it all: auteur cinema from the Nouvelle Vague onwards, fashion, and ideal beauty and elegance: Catherine Deneuve – no one else.

Julianne Moore

An extraordinary actress who worked with some of the most beloved and celebrated directors of modern cinema. A person of charm, intelligence, and curiosity, she is deeply in love with cinema. She quickly got involved and was passionate about her role as jury president. I know she will be great at it.

Featured image: Rocio Muño Morales and Alberto Barbera, credits La Biennale di Venezia – Foto ASAC ph. Giorgio Zucchiatti