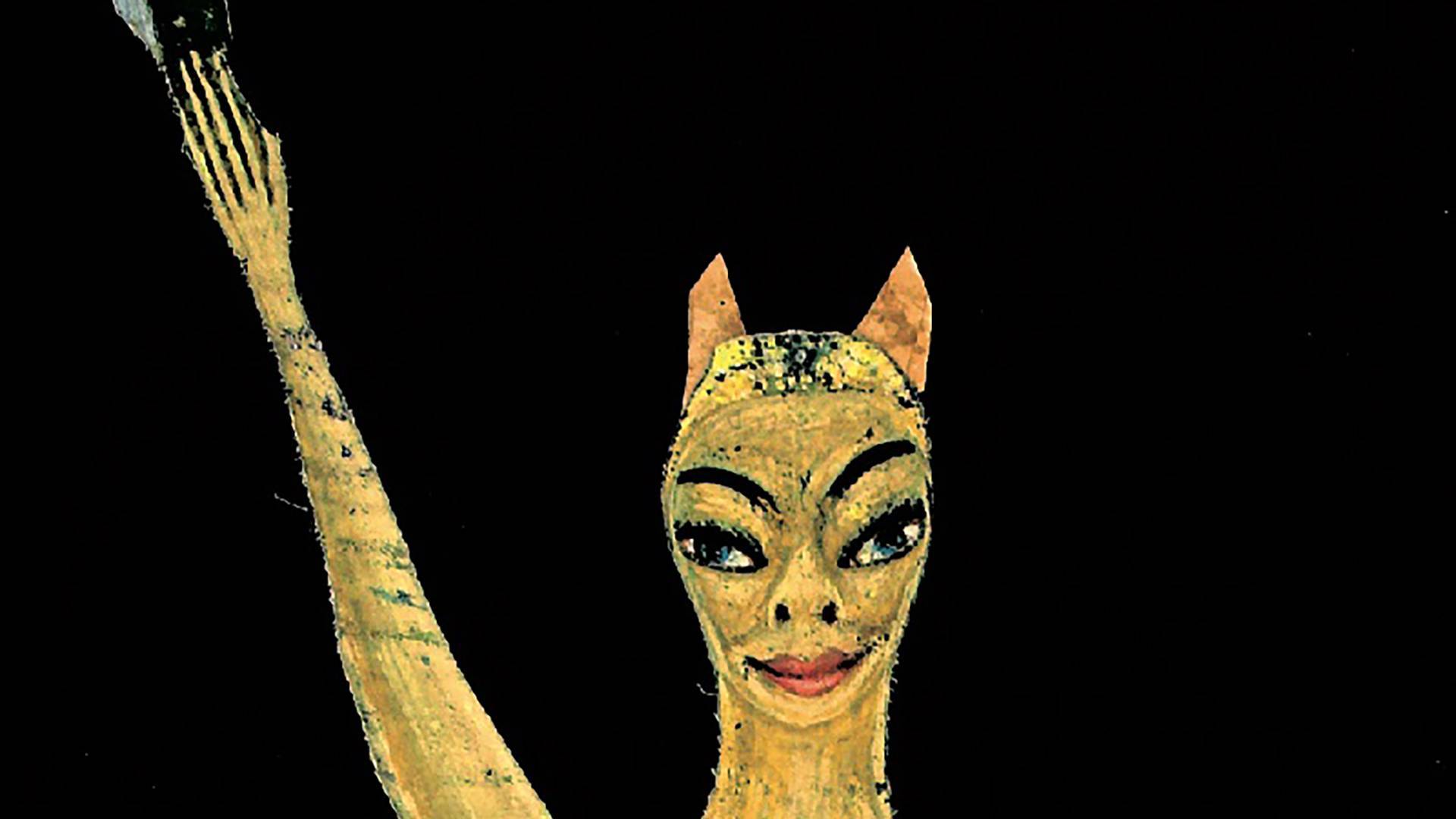

213 artists from 58 countries, 180 of them are participating for the first time in the 59. International Art Exhibition. 1433 works and objects, 80 new projects are conceived specifically for the Biennale Arte 2022. The Milk of Dreams takes Leonora Carrington’s otherworldly creatures, along with other figures of transformation, as companions on an imaginary journey through the metamorphoses of bodies and definitions of the human.

An exhibition conceived in a fully unusual time. You worked on the construction of The Milk of Dreams in your house in New York and referring to that period you used the very evocative expression “an end of the world intimacy”. What did your relationship with the invited artists take away from you and what did it give you?

It was really very complicated. First of all, it must be said that I have never curated such a large exhibition before. Just four weeks after I was appointed we started to experience the unique and extraordinary conditions that we all know well and that led the Biennale to postpone the Exhibition by one year. From a curatorial and research point of view, I certainly cannot say that this was a negative aspect, all the contrary. Unlike my forerunners I had more time to study, to learn, to know artists better, even if often only virtually. At the same time, however, I am fully and painfully aware of having missed one of the most beautiful and exciting aspects of the whole work process, that is to travel and meet the artists, perhaps even in countries that I knew and know very little. Unfortunately I could not do it. From this point of view, the construction itinerary to this huge exhibition was therefore rather complex and limiting. However, I managed to put together a team of people who helped me conduct research in areas where I knew I couldn’t get to, and although it wasn’t the same thing, I finally made it. Just a few days from the opening I have a strange feeling related to the fact that I could not see all the works in first person. I have seen only some videos or photos of some of the works which will be exhibited and, therefore, I can only hope that there will be no surprises! And if there were to be, well: these will also be part of The Milk of Dreams.

The Milk of Dreams by Leonora Carrington contained in itself everything I was working on: the magic, the metamorphosis, the idea of the clash between man and machine…

The title of the exhibition, The Milk of Dreams precisely, is taken from a small apparently simple book of illustrated tales which opens on an infinite world of suggestions evoked by the author, the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington. What is the deep meaning of this choice? Why did you choose Carrington herself?

Surrealism has fascinated me since my university days, although in that specific academic context you often have to study mainly the ‘male’ side of this extraordinary movement. In the past few years some very important international surrealist exhibitions played a major role in generating an in-depth study about some surrealist women artists such as Leonora Carrington, as well as Remedios Varo, Leonor Fini and many others. I let myself be carried away by the pleasant rediscovery of these artists who are as good as their male colleagues but who are not recognized and appreciated in the same way. I had known Carrington as an artist for some time but during my preparation of the Biennale I had the opportunity to get fond of Carrington as a writer. I read all her novels and her wonderful stories. One of my favorites is The Hearing Trumpet. The main characters are two old women who rebel against the idea of the nursing home and begin to practice magical rites of witchcraft. It is the portrait of a rebellious and happy old age we are not used to read in books or see in movies, where usually this last phase of our existence is represented as a mere end-of-life, or as an illness. Then I came across her little book of children’s stories, and it was a real revelation to me: suddenly it was like I was able to see all my interests, it was like a deep physical intellectual sight. The Milk of Dreams contained in itself everything I was working on: the magic, the metamorphosis, the idea of the clash between man and machine… At that point I couldn’t do anything else but ‘steal’ its title and use it. So, I didn’t start from Leonora Carrington or her book. It was like if at some point in the process of preparing the Biennale I simply realized that this was the right title for it.

If The Milk of Dreams seems to be a sort of final catharsis, can we say that the starting point of this curatorial project is in some way very similar to the itinerary of The Magical World, the title of the Italian Pavilion 2017 that you curated? Is there a thread that links the two projects?

I have always been very fascinated by everything related to the dream, to the magical and unconscious world. However, should there be any evolutive development between the 2017 project and the current one, it may have developed exclusively on an unconscious level. I haven’t planned it, everything started in a very natural way. I began to realize that there is a link with The Magic World only during the press conference for the presentation of The Milk of Dreams, from the moment I actually started talking about it. They are two reflections developing from two completely different ideas: the Italian Pavilion had a more anthropological character presenting some specific Italian rituals illustrated by Ernesto de Martino, on the contrary the curatorial aspect of this exhibition is based on a wider and more articulated idea. Even if in a way, the two projects have the same spirit. In both cases it is not a question of seeking refuge in the unconscious or the dreamlike world to escape from reality, but rather of finding some methods to live and to look at the world in a different way than the Western or the rational one. To put into practice something subversive, magical, indigenous, or anyway something which goes beyond our present common feeling doesn’t lead to something irrational but to a different point of view which allow us to interpret in a different way everything surrounding us. This can be considered the common features between the two projects.

The contemporary is often seen as a “spaceship” detached from what preceded it, as if it were an entity out of time. In this exhibition you want to give people a key to read today’s art through historical traces which help to make it easier to read, understand what has been achieved and exhibited by the selected artists. Let’s talk a bit about these five highly anticipated, fascinating time capsules, a sort of time stations scattered throughout the long journey of the exhibition. How do you explain this choice?

First of all, I wanted the Biennale and this one in particular to be not just a simple picture of the artistic works produced in the last two years but also a sort of “zoom out” allowing my exhibition and the previous ones to be part of a single great story. It is not enough to say that the Biennale is the oldest art exhibition in the world: it is essential to give a concrete, tangible meaning to such a statement by creating some possible links between what it proposes today and what it has proposed in past editions. Very often I mention the Biennale of 1948 because it was in some way the “Biennale of rebirth” after four years of interruption due to World War II. A historical context which is certainly very different from ours, much more tragic. Yet we can find some common elements between that tragic past and our present. In fact, they are both an expression of a sharp rupture in the ordinary flow of our individual and social existence. Today as in that specific moment of our history we need urgently to experience something new and at the same time to go back to those languages which have been ignored, deleted or banned in the last few years. I was therefore interested in speaking also of the historical moment because in this period you can feel a cultural excitement from many institutions which are wondering whether their own collections and exhibitions really represent our identity, or if we need to re-examine the circumstances the works have come from. An extremely important process of rewriting and re-questioning history is underway. This is what makes every cultural institution alive today. We don’t have to look at the Biennale as a monolith, but we have to pay attention to omissions and to what has been often unconsciously censured. This approach characterizes a process which is developing a bit everywhere all over the world.

Let’s enter now these historical capsules, starting from the first one The Cradle of the Witch and its surrealist visions. What is the meaning of this symbolic retrieval? What are the imprints left by these women artists who are still so actual?

As I said before I have been pursuing an interest in Surrealism for a long time. My graduation thesis was focused on the year 1929, even if its main subject was the French philosopher Georges Bataille and his magazine “Documents” which was extremely critical of the Surrealist movement. Today Surrealism seems to be very actual again as shown by the great number of exhibitions on this movement in many museums around the world, such as Tate and MET. We can say that something extremely concrete is happening. Let’s think about the context in which also the second Surrealism was born, at the beginning of World War II. European society was experiencing a highly reactionary turning point, something that unfortunately we have been experiencing again in the past few years, although not on such a large scale. The tragic and unexpected outbreak of the war in Ukraine has made all this even more dramatically tangible. It may sound like a risky statement but maybe artists are using again some methods typical of the Surrealist movement just because we are living in a similar context. Going back to introspection is something unavoidable in a period of crisis. At the end of two years of pandemic which obliged us to stay at home, the most natural thing an artist can do is to try to analyse the world tragedies through a more personal, dreamlike, and surreal vision of the present.

All this converges in works that today seem to be very simple, but at that time they were incredibly contemporary and futuristic, because they used in a surprising way the charming power of new technologies.

In the second time capsule entitled Technologies of Enchantment you propose an itinerary through the twentieth century art of which perhaps we have not grasped the full scope in all its facets, like for instance the essential lesson of the movements in the 1960’s. Technology and perception, the relationship between a work and its audience are all themes that we are now investigating in the new digital frontiers. What did enchantment of technology mean yesterday and what does it mean today?

When I refer to technology, I talk about it as broadly as possible. I’m not particularly interested in VR or any expression of digital research in particular. What intrigues me, what stimulates my curiosity and my imagination is the charming power that technological innovation has had over time on artists. The current means are very different from those of the 1960’s but the power of the new discoveries which inspires the artists and their minds is the same. Let’s look at kinetic art, programmed art and at the introduction of new technologies such as computers, but also at the use of new materials, such as plexiglass or neon… All this converges in works that today seem to be very simple, but at that time they were incredibly contemporary and futuristic, because they used in a surprising way the charming power of new technologies. I therefore wanted to give space to a group of Italian women artists who in those years were already reflecting on an idea of interface, membrane, screen, epidermis, concepts that inspire many contemporary artists. These are very strong current themes and I wanted to bring them back to a language that has existed for decades but that had been so far dealt with only marginally, especially as far as these six artists – Grazia Varisco, Laura Grisi, Nanda Vigo, Marina Apollonio, Lucia Di Luciano, Dada Maino – present in the capsule are concerned.

How is the enjoyment of art changing with the occurrence of new digital media that have occupied us so much?

I have been working for ten years at the High Line in New York and this means first of all to think how to communicate with the eight million people who pass by there not necessarily because they want to visit a museum but because they are searching for art. And it is here that the curator takes his/her role, i.e. to make art works understandable and enjoyable in a context where anyone can have their own access. An art work reaches its function when it opens up to many points of views and different interpretations which are capable of ‘tickling’ the intellect and stimulating strong reactions, even one of disgust, why not. What matters is that these art works have their own important emotional value. This is the artist’s work, of course; but it is also the curator’s work. Our goal is to create stimulating paths for everyone.

The history of the Biennale, already investigated by The Disquieted Muses exhibition, seems to play a very important role in the overall economy of your exhibition itinerary. The reference to the visual and concrete poetry of the exhibition Materialization of Language set up for the Biennale Arte 1978, that is again found in the capsule dedicated to the Orbiting Body, is revealing in this regard. How does this digging work in the ASAC deposits lead to re-read and re-write parts of twentieth-century art and which of these traces are still present today?

It was an extreme privilege for me to have a whole year to carry out my study and it was a great experience to dig into the ASAC archives, even though unfortunately it was not possible to go there physically. Surely the research work done for The Disquieted Muses influenced my decision to include historical works in ‘my’ Biennale, works which are not necessarily coming from the ASAC, but which are all able to induce a reflection on the different cycles of the history of the Biennale and on how the Institution itself reacted to the great ‘cataclysms’ of history: wars, social revolutions, floods. I have always been very passionate about Visual Poetry and Concrete Poetry as well. These art forms which have spanned the last two centuries of our history, have taken on a new value today. I tried to convey that kind of artistic expression and the dialogue that it is able to establish with the contemporary through the third capsule, which brings together artists, women artists and women writers who since the ‘800 have used expanded forms of language as a tool of emancipation and who have imagined new ways of being through their life stories.

The thought of the American philosopher Donna Haraway, a theorist of a branch of feminist thought that studies the relationship between science and gender identity, accompanies the line of the capsule dedicated to works that represent containers, the “vessel”, presumably a reference to the object-container as a female archetype. In an exhibition that roots out gender barriers, with a preponderant participation of female artists, how has the ‘feminine’ aspect guided your curatorial project?

I don’t necessarily think it’s the most feminine or feminist capsule. It is certainly the least historical capsule, in the sense that if the others in a certain way are connected to a particular artistic movement, be it Futurism, Surrealism or Bauhaus, this one is more metaphorical. I would call it an iconology of vessel-forms and their symbolic, spiritual and metaphorical links with nature, including in a transversal way works ranging from 1600 onwards. The idea for the vessel capsule has come from The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, a booklet by visionary science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin that I read almost by chance because I was lured by Donna Haraway’s preface. Le Guin’s text offers a very fascinating reinterpretation of the origin of technology and, at the same time, of narration and fiction. The first technological invention, says Le Guin, is no longer to be found in the weapons used by the hunting men, but rather in the containers women used to hold in their hands or in a bag while collecting grains and seeds. Therefore, the container is here seen as the first example of technological invention. Starting from this first assumption, Le Guin expands his analysis to the great narratives, such as the Promethean or the mythological ones, which should be reviewed precisely because they resemble large bags in which letters, phrases and stories intersect symbiotically.

My interest in the posthuman comes from my readings, but it is evident that this topic is also widely attracting artists. These are issues that are becoming more and more topical.

In her book The Posthuman (2013) the philosopher Rosi Braidotti says: “The posthuman condition makes us think critically and creatively about who and what we are actually becoming”. One of the strongest suggestions of your program, which we find in the last capsule entitled The Seduction of a Cyborg, concerns precisely the end of the centrality of the human being, his becoming a machine, a land. Why is this issue so urgent?

My interest in the posthuman comes from my readings, but it is evident that this topic is also widely attracting artists. These are issues that are becoming more and more topical. The cultural setting of our society, which puts the man at the centre and at the top of the pyramid and everything else below him, is to be reconsidered in the light of the last two years of the pandemic which have exhibited very clearly the fragility and mortality of our bodies. We must seek a different relationship with other people but also with other species and with the world around us, as if we had reached a point of no return. And it’s not just Rosi Braidotti who says it. In fact, a lot of intellectuals now argue that the time has come not only to imagine, but also to actualize a different relationship linking us to nature and to other species. It is becoming essential to take a step back, to realise that we are no longer at the centre of the world and to set our existence on sharing and on symbiosis, disconnecting ourselves from the most obvious and pre-eminent manifestations of capitalism devoted to exploiting the resources of the planet and nature without any hesitation. We must imagine a more horizontal world, governed by equal relations and coexistence between species.

The five capsules therefore present decidedly strong themes, which involve the existential sphere of all of us. But when we leave the Biennale will we be more optimistic or pessimistic?

A bit both. I do not want to say that we will only be optimistic, because there will also be dark and disturbing works, but the great strength of art and artists is to digest the dramatic crisis of recent years and to propose it again in a creative key, which will be more optimistic or more pessimistic depending on the personal visions of each one. It is a process of revisiting that takes the form of a very important exercise, even if it is up to the visitor to draw his own conclusions. Our job is to create the conditions to be able to talk about urgent issues. The fact that we can start to confront, or at least to have a different awareness, I think is essential. The role of the press and literature, as well as of exhibitions is to absorb the turmoil and concerns of each era and translate them into a visual way for the public.

Cecilia Vicuña and Katharina Fritsch. What do these two artists, that you have chosen to reward with the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, represent for you?

Katharina Fritsch is an incredible artist, just like Jeff Koons and Charles Ray, although unfortunately she is not recognized in the same way, despite having imprinted in sculpture some innovations of language if not before, certainly in the same years as her male colleagues. She is an artist who still has a charge and an extraordinary desire to say and create regardless of fashions or trends, carrying out a very unitary and serious work. Cecilia Vicuña works with a type of sculpture that finds in the fragile collage of simple objects the poetry, of which she is a great representative, being herself a poet and having worked for decades as an editor of South American poems that would otherwise have been lost. They represent two very different and in some ways opposite visions: on the one hand Fritsch’s sculpture which is ‘super-produced’ also in innovative, industrial and complex ways; on the other hand, Vicuña’s ‘precarious’ sculpture, which is born from the encounter/clash of small objects in nature, in public space.

The black and distressing shadow of war is of course also affecting culture and art. The Russian Pavilion will remain closed, while there will be Ukrainian participation in the Arsenal. Russian and Ukrainian artists are present in the main exhibition. There has been much talk in recent weeks, with often opposite and conflicting ideas, about the opportunity or not in such a dramatic moment to involve institutions and artists from the territory, from the country which has provoked this war, namely Russia. How do you cope with this issue that certainly confronts us with the theme of the limitation of freedom of expression, a freedom art has always fed on more than any other form of communication?

The war has confronted us with a dramatic situation at the point that talking about art today seems almost superficial and useless. I am convinced that artists and artistic institutions must have the courage to take a political position, but I firmly believe in art as a means of maximum freedom of expression. Maybe some people can feel a sort of immediate satisfaction in censoring Russian art at this time, as it has happened in various areas these days especially on social channels, but it is an ephemeral satisfaction; that kind of ‘happiness’ which lasts just a second and which gives no place to critical reflection. It is much more useful and interesting to create spaces for discussion to better understand the condition of the artists involved, their position, which at this time is definitely difficult. The case of the Russian Pavilion is a bit different and goes far beyond art, as the Pavilions and the artists exhibiting in the Biennale spaces institutionally represent their own countries. In this sense I can understand very well the artists and the curator of the Russian Pavilion who have decided to withdraw. I managed to get in touch with the Russian artist who is present in the main exhibition, Zhenya Machneva. She couldn’t have her visa yet and unfortunately she was having huge problems to leave her country. We are daily in contact with the Ukrainian Pavilion and, thank goodness, both the curator and the artist, together with their work, have managed to leave their country. The Biennale is doing its best to help them. The Pavilion will certainly be there, and we hope to be able to do something else, to support them in other ways. As futile as it may seem to think of the Biennale at such a time, to be able to deal with this project means for them to recover a certain normality amid sadness and despair. As symbolic as it may be, this is a real value for them. Our priority currently is to be able to guarantee the presence of the Pavilion as well as to give maximum support and solidarity to Ukrainian artists.

Historical contingencies have often put back at the center of the debate the opportunity of a division into national pavilions of a major international exhibition such as the Biennale. A structure that on the other hand is a bit the backbone of this major exhibition of contemporary art. How do you fit inside this “architecture”?

I do not find the structure of the national pavilions obsolete at all. We have often seen many countries use their pavilion to talk about urgent and universal issues. Of course, it is a structure that comes from a twentieth-century vision of international relations; a vision which is perhaps obsolete today but ceases to be such as soon as we witness an invasion of one country by another … That’s when the national pavilions leave the sphere of the symbolic and become extremely real and current.

The Milk of Dreams is a world populated by fantastic stories, hybrid and mutant beings, a world where anyone can transform. What would Cecilia Alemani wish to turn into? What is your Milk of Dreams?

What would I like to turn into? At this moment I would say into a cloud, to fly up, far and light amid silence. I see myself as a surrealist cadavre exquis, made up of many disconnected pieces that try to talk to each other but without too much success. I can’t say exactly what my Milk of Dreams is. I think it’s art of course, it’s to be able to ‘splash around’ in the artists’ works.